Conditions That Cause Dry Skin

Dr. Kate Dudek • September 28, 2022 • 5 min read

The skin plays a very important role, acting as a barrier between the outside of the body and the inside. It is comprised of three layers, the epidermis, the dermis and the hypodermis. The epidermis is the most superficial; forming a literal barrier from the elements, the cells within this layer are constantly renewed. Underneath this layer lies the dermis, which is responsible for providing much of the skin’s mechanical strength. The third and deepest layer is the hypodermis; with pockets of adipose tissue, this layer provides insulation and protection to the underlying organs.

The skin composition is not consistent across the body; it is thicker in areas such as the soles of the feet and palms of the hands, which get more mechanical use. It also varies in laxity, mechanical strength, pH and moisture.

Dry skin, known medically as xerosis, is very common. It affects males and females of all ages. One of the main symptoms is itching, this is often accompanied by flaky skin, cracking and patches of dryness, which causes the skin to feel tighter and rough. Dry skin is usually caused by a lack of moisture in the epidermal layer. As well as being protective, this layer contains lipid molecules and very specific proteins, including filaggrin, which prevent dehydration. Genetic conditions can affect the function of these proteins, resulting in a loss of water retention in the epidermis, and causing the skin to become dry and sensitive.

The skin is a very valuable tool with regards to informing on a person’s health, and its structure has been shown to degenerate in response to aging, obesity and some diseases. This article aims to review some of the most common conditions that challenge the integrity of the skin by exploring how the skin is altered and what measures can be implemented to alleviate the symptoms.

Atopic dermatitis (eczema)

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory disease, characterised by persistent itching. It is the most common type of eczema and usually starts during childhood. Most people outgrow the condition, although their skin remains sensitive and highly susceptible to irritation.

The exact pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis is unknown; however, it is thought to involve a complex interplay between dysfunction of the skin barrier (genetic or environmental), a faulty immune response and hypersensitivity of the subcutaneous layer of the skin. One gene known to be involved is filaggrin, which, under normal conditions, maintains hydration of the skin. The involvement of at least one mutated gene explains why atopic dermatitis appears to run in families. The heightened sensitivity of the skin is likely to be caused by an increase in the density of epidermal nerve fibres lying under the surface of the skin.

Most patients with atopic dermatitis will find that there are certain triggers that exacerbate their condition; these can include soaps, detergents, cosmetics, wool, dust and sand. Furthermore, stress, whilst not considered to be causative, certainly seems to worsen the symptoms.

Some of the most frequently observed symptoms are redness, swelling, blisters, cracked skin and weeping sores. Dry skin is very common and any inflammatory response is made worse by scratching. Persistent itching can be very detrimental to a person’s quality of life, thus finding a way of alleviating the sensation is very important. One option is to use an emollient-rich moisturiser, applied to damp skin, which inhibits the evaporation of water. This is actually best done as a preventive treatment, so prior to, or in anticipation of, a flare up. Using a moisturiser that is designed for use on sensitive skin will hopefully avoid further problems.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune condition, believed to affect up to 2% of the population. In its most common form, psoriasis vulgaris, plaques of thickened scaly skin are visible on the elbows, knees and scalp. The silvery-white flakes that are usually seen are due to rapid proliferation of the underlying dry skin cells. It is usually diagnosed in early adulthood, however can affect both men and women of any age.

The exact cause of psoriasis is not known. It is thought to be due to a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors, which leads to an over-active inflammatory response in the skin. Psoriasis often co-presents with joint pain and arthritis, meaning management of the condition frequently involves a multi-disciplinary team, that includes dermatologists and rheumatologists. The condition also has a strong association with other inflammatory conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, highlighting a need for regular monitoring.

Whilst not curable, the symptoms of psoriasis can be managed and patients often go into remission. One major factor is the impact that the condition can have on a patient’s quality of life, with many finding that the appearance of their skin negatively affects their self confidence.

Mild cases of psoriasis may respond well to treatment with topical lotions, including mild steroid creams and moisturisers. For those with a more severe form, UV therapy, steroid injections and medications are all viable treatment options. If the scalp is affected, special psoriasis shampoos can be effective. Recent developments in terms of psoriasis treatment are biologic therapies, which are usually given in the form of antibodies, which target the parts of the immune system that are over-activated in psoriasis patients.

Hypothyroidism

Approximately 12% of people will experience a problem with their thyroid gland during their lifetime and women are eight times more likely to be affected than men. Hypothyroidism results from an underactive thyroid gland, meaning that insufficient levels of thyroid hormone are produced. It can be a difficult condition to diagnose as symptoms are often non-specific and easily attributable to other disorders. Some of the most frequently observed symptoms are tiredness, weight gain, generalised weakness, heavy or irregular periods and itchy dry skin.

In one study, more than 70% of hypothyroid patients reported dry skin, suggesting it is one of the most common symptoms. Low levels of thyroid hormone result in a slow down of metabolism, which causes reduced sweating (sweat is the body’s natural moisturiser), and means that the body’s cells have less capability to repair and replace themselves. This has a major impact on cells with a rapid turnover rate, including hair and skin cells. The skin becomes rough and the epidermal layer thins. Skin on the soles of the feet and palms of the hands becomes particularly dry.

Prompt identification of changes to the skin can be lifesaving; myxedema is a serious complication of untreated hypothyroidism. One of the first signs is a red, swollen rash. Immediate medical aid should be sought in cases of suspected myxedema.

Fortunately hypothyroidism is treatable, usually with synthetic hormone tablets. Restoring levels of thyroid hormone should alleviate most of the symptoms, including problems with the skin. In the meantime, dry skin can be soothed using a humectant-rich moisturiser.

Diabetes

Diabetes is a chronic condition characterised by high blood sugar levels. Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas which regulates blood sugar levels, preventing them from getting too high. Diabetes is caused by either insufficient insulin production (type 1 diabetes) or the inability of the body to use insulin properly, resulting in insulin resistance (type 2 diabetes). Some women experience gestational diabetes during pregnancy because the hormones produced by the placenta induce insulin resistance. This type of diabetes is controlled by diet and usually disappears post-childbirth, although women who have experienced it are at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life.

Patients with type 2 diabetes may be able to control their condition with their diet. However, those with type 1 diabetes will require lifelong insulin treatment.

Some of the most common symptoms of diabetes are increased thirst, frequent urination, unexplained weight loss despite an increased appetite, fatigue, blurred vision and regular infections. The skin is particularly affected in diabetes, and there are a number of skin conditions associated with diabetes, collectively named diabetes dermadromes. Between 40-70% of diabetic patients experience some form of skin pathology. The skin becomes particularly prone to both bacterial and fungal infections, as well as patches of localised itching and dry skin (xerosis). It is still not fully understood why diabetes has such a profound effect on the skin, however, one proposed theory for why so many patients experience dry skin is that the body is using all the water it can to get rid of the excess blood sugar. Other factors thought to be involved include an altered immune response, nerve damage and changes to the structure of the collagen located within the epidermis.

A good moisturiser will prevent further moisture loss and provide soothing relief to skin that is uncomfortable and inflamed. Infections cause the skin to become hot, swollen, red and easily aggravated. Whilst these infections are highly prevalent in patients with diabetes, following a good skin care routine can reduce the risk. Mild soaps and moisturisers are recommended to ease the burden of regular infections.

Some skin conditions are particularly prevalent in those patients with diabetes, these include diabetes dermopathy and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, which both cause brown scaly patches; acanthosis nigricans, which is a form of hyperpigmentation; and diabetic blisters, which resemble burns, although are usually painless. Treatment options for necrobiosis lipoidica include UV light therapy, low-dose aspirin and corticosteroids. For acanthosis nigricans and diabetic blisters the best treatment option is typically to control blood sugar levels through diet or synthetic insulin.

Hormonal changes (pregnancy and the menopause)

Striae gravidarum (stretch marks) and hyperpigmentation occur in up to 90% of pregnancies. Both are thought to be due, in part, to hormonal changes, specifically increased levels of oestrogen and relaxin. Stretch marks are pink and purple lines that form across the expanding abdomen, breasts, buttocks and thighs. Much maligned by the majority of women who are affected, the beauty industry readily markets most pregnancy-related products as ‘stretch mark treatment’, however, scientifically there is little evidence that they actually work. Hyperpigmentation usually affects the areolae or genitalia. A particularly common manifestation of the condition is the linea nigra, which appears down the centre of the abdomen. Some pregnant women experience a form of hyperpigmentation on the face, known as melasma, or the ‘mask of pregnancy’. As with stretch marks, there is no medically approved cure, although most skin tone changes will resolve following delivery. It is recommended to avoid excess sun exposure as this can exacerbate the condition.

During pregnancy, existing skin conditions may worsen or improve. One study found that for pregnant women with atopic dermatitis, approximately half saw a worsening of symptoms and a quarter saw an improvement. The symptoms of psoriasis usually improve during pregnancy. The reason for these changes in some women, but not others, remains unclear, however, a hormonal link is likely.

Pregnant women are also at increased risk of developing rashes, usually accompanied by dry, itchy, uncomfortable skin. Examples include pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPP), which is a form of dermatitis, and intrahepatic cholestasis, which can cause intense itching. The former is relatively harmless, treated with antihistamines and usually resolves following delivery. The latter can be very serious, causing premature delivery or foetal distress and, thus, requires careful monitoring.

Itchy, dry skin during pregnancy can be treated with gentle moisturisers.

Pruritus, or itchy skin, starts during the perimenopause, which is the period of time that precedes the menopause. Generally considered to occur in response to reduced levels of oestrogen, the skin produces less collagen and fewer natural oils. The net result of this is thin, dry, itchy skin that has less elasticity. Some menopausal women also experience a flare up of existing skin conditions, such as psoriasis, usually attributed to a change in hormone levels. Evidence for this comes from the correlation between higher oestrogen levels during pregnancy and improved psoriasis symptoms, compared with lower oestrogen levels during the menopause and a worsening of symptoms. Many women choose to alleviate their menopausal symptoms with hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Restoring oestrogen levels counteracts many of the negative effects attributed to the menopause, including improving skin tone and texture.

Humectant-rich moisturisers can also provide soothing relief to uncomfortable skin and it is proven that certain nutrients, such as vitamin C, can enhance the body’s production of collagen.

Pregnancy and the menopause can both trigger acne. This is best treated with gentle cleansers and a good skin care routine.

Age

With increasing age comes mechanically fragile skin that can be very dry and lacking in elasticity. Cellular processes slow down naturally with age, which impairs certain physiological functions, such as wound healing; this makes blemishes and scars more visible. Wrinkles form because skin laxity is lost due to reduced collagen production. Most of these changes are thought to also be due to reduced hormone levels. Adopting a good skin care routine, can lessen the physical signs of aging, as can taking steps to implement a healthy lifestyle. Avoiding excess alcohol and smoking, eating a balanced diet, exercising more, applying sunscreen regularly and getting plenty of sleep are lifestyle changes that everyone could benefit from. In combination, adopting these good practices will help to improve your overall health, in addition to enhancing the appearance of your skin.

Medication

Chemotherapy can have quite a drastic effect on the skin. A number of the most common chemotherapeutic agents in use today can cause fragile and extremely dry skin. The constantly regenerating skin cells are vulnerable to attack by cancer drugs which are designed to target rapidly reproducing cells. The skin barrier is compromised, lessening its protective abilities against environmental insults, resulting in immune activation and leading to a heightened reaction to irritants.

One way of combating the negative effects that chemotherapy may have on the skin is to use emollient-rich moisturisers. The Cancer pack is designed to help those women who are undergoing treatment for cancer. With a specially-designed formulation, rich in humectants, it provides moisture to painful, dry skin, and brings soothing relief to areas of inflammation.

For a comprehensive review on the effects of chemotherapy on skin, click here.

Medication used to treat high blood pressure (antihypertensive drugs) can cause a range of side effects, including headaches, tiredness and skin rashes. Other frequently prescribed drugs that can adversely affect the skin include diuretics, beta blockers, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers. Due to the possibility of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), lifestyle changes are recommended as the first line treatment approach.

The most common dermatological side effects are rashes and eczema. In fact, eczema is responsible for half of the reported skin ADRs caused by hypertensive drugs. Pre-existing conditions, such as psoriasis, may also be aggravated. Management will depend on the severity of the symptoms. If the side effects become intolerable an alternative medication may need to be prescribed. For milder effects, moisturisers may provide adequate relief.

Antidepressants can also cause adverse skin reactions. The newer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally better tolerated than the older tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), however, dry skin, acne and increased sensitivity to the sun are all common side effects. One skin complaint seen with SSRIs is erythema multiforme, which causes a rash that resembles ‘bull’s eye’ patches to appear. Normally fairly mild in nature, rashes should be monitored regardless, because they can be an early warning sign that a patient is developing hypersensitivity to a particular drug. If this is the case, an alternative treatment may be required.

For the majority of medications it is impossible to predict how well a patient will tolerate both the drug itself and the side effects. Skin rashes and their related pathologies are a common side effect to many medications in use, although fortunately they are usually relatively mild and manageable. Provided quality of life is not impacted and the skin reactions remain mild, the optimum approach for controlling them is to adopt a good skincare routine, using gentle moisturisers, rich in antioxidants. Choosing a product with natural SPF protection is also recommended.

Sources:

- Calleja-Agius, J, and M Brincat. “The Effect of Menopause on the Skin and Other Connective Tissues.” Gynecological Endocrinology, vol. 28, no. 4, Apr. 2012, pp. 273–277., doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.613970.

- Canaris, G J, et al. “Do Traditional Symptoms of Hypothyroidism Correlate with Biochemical Disease?” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 12, no. 9, Sept. 1997, pp. 544–550.

- Ceovic, R, et al. “Psoriasis: Female Skin Changes in Various Hormonal Stages throughout Life—Puberty, Pregnancy, and Menopause.” BioMed Research International, no. 2013, 2013, p. 571912., doi:10.1155/2013/571912.

- Hall, G, and T J Phillips. “Estrogen and Skin: the Effects of Estrogen, Menopause, and Hormone Replacement Therapy on the Skin.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, vol. 53, no. 4, Oct. 2005, pp. 555–568., doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.039.

- Herstowska, M, et al. “Severe Skin Complications in Patients Treated with Antidepressants: a Literature Review.” Postepy Dermatologii i Alergologii, vol. 31, no. 2, May 2014, pp. 92–97., doi:10.5114/pdia.2014.40930.

- Kabashima, K. “New Concept of the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis: Interplay among the Barrier, Allergy, and Pruritus as a Trinity.” Journal of Dermatological Science, vol. 70, no. 1, Apr. 2013, pp. 3–11., doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.02.001.

- Kemmett, D, and M J Tidman. “The Influence of the Menstrual Cycle and Pregnancy on Atopic Dermatitis.” British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 125, no. 1, July 1991, pp. 59–61.

- Nest

Download the Nabta App

Related Articles

9 Natural Induction Methods Examined: What Does the Evidence Say?

Towards the end of [pregnancies](https://nabtahealth.com/article/ectopic-pregnancies-why-do-they-happen/), many women try methods of natural induction. The evidence supporting various traditional methods is variable, and benefits, side effects, and notable potential health risks are present. Understanding what science says can help individuals make informed choices in consultation with a provider. Induction of Natural Labour induction Myths, Realities and Precautions ---------------------------------------------------------------------- The following section will review nine standard natural induction methods, discussing the proposed mechanism, evidence, and safety considerations. Avoid potential hazards by avoiding risky labor triggers and get advice from your [obstetrician](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/obstetrician/) before choosing any method mentioned below. Castor Oil ---------- Castor oil has been used throughout the centuries to induce labor, and studies suggest that it does so on some 58% of occasions. This oil stimulates prostaglandin release, which in turn may have the result of inducing cervical changes. Adverse effects, such as nausea and [diarrhea](https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diarrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20352241), are common, however. Castor oil should be used near the [due date](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/due-date/) and with extreme caution, given its contraindication earlier in pregnancy. Breast Stimulation ------------------ The historical and scientific backing of breast stimulation is based on the release of oxytocin to soften the [cervix](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cervix/). A study has shown that, with this method, cervical ripening may be achieved in about 37% of cases. However, excessive stimulation may cause uterine hyperstimulation, and guidance from professionals may be essential. Red Raspberry Leaf ------------------ Red raspberry leaf is generally taken as a tea and is thought to enhance blood flow to the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/) and stimulate [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/). Traditional use, however, is tempered by a relative lack of scientific research regarding its effectiveness. Animal studies have suggested possible adverse side effects, and no human data are available that supports a correlation with successful induction of labor. Sex --- Sex is most commonly advised as a natural induction method based on the principle that sex introduces [prostaglandins](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/prostaglandins/) and oxytocin, and orgasm induces uterine [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/). The few studies in the literature report no significant effect on labor timing. Generally safe for women when pregnancy is otherwise low-risk but may not speed labor. Acupuncture ----------- Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese practice that has been done to stimulate labor through the induction of hormonal responses. However, some studies show its effectiveness in improving cervical ripening but not necessarily inducing active labor. An experienced practitioner would appropriately consult its safe application during pregnancy. Blue and Black Cohosh --------------------- Native American groups traditionally utilize blue and black cohosh plants for gynecological use. These plants are highly discouraged nowadays from inducing labor because of the risk of toxicity they may bring. Although they establish substantial [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/), they have been observed to sometimes cause extreme complications-possibly congenital disabilities and heart problems in newborns Dates ----- Some cultural beliefs view dates as helping induce labor by stimulating the release of oxytocin. They do not help stimulate uterine [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/) to start labor, but clinical research does support that dates support cervical [dilation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/dilation/) and reduce the need for medical inductions during labor. They also support less hemorrhaging post-delivery when consumed later in pregnancy. Pineapple --------- Something in pineapple called bromelain is an [enzyme](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/enzyme/) that is supposed to stimulate [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/) of the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/). Animal tissue studies have determined it would only work if applied directly to the tissue, so it’s doubtful this is a natural method for inducing labor. Evening Primrose Oil -------------------- Evening Primrose Oil, taken almost exclusively in capsule form, is another common naturopathic remedy to ripen the [cervix](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cervix/). Still, studies are very few and indicate a greater risk of labor complications, such as intervention during delivery, and it is not recommended very often. Safety and Consultation ----------------------- Many of these methods are extremely popular; however, most are unsupported by scientific data. Any method should be discussed with a healthcare provider because all may be contraindicated depending on gestational age, maternal health, and pregnancy risk levels. Try going for a walk, have a warm bath and relax while you’re waiting for your baby. “Optimal fetal positioning,” can help baby to come into a better position to support labor. You can try sitting upright and leaning forward by sitting on a chair backward. Conclusion ---------- Natural methods of inducing labor vary widely in efficacy and safety. Practices like breast stimulation and dates confer some benefits, while others, such as those involving castor oil and blue cohosh, carry risks. Based on the available evidence, decisions about labor induction through healthcare providers are usually the safest. You can track your menstrual cycle and get [personalised support by using the Nabta app](https://nabtahealth.com/nabta-app/). Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you. Sources : 1.S. M. Okun, R. A. Lydon-Rochelle, and L. L. Sampson, “Effect of Castor Oil on Induction of Labor: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 2023. 2.T. K. Ford, H. H. Snell, “Effectiveness of Breast Stimulation for Cervical Ripening and Labor Induction: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2023. 3.R. E. Smith, D. M. Wilson, “Red Raspberry Leaf and Its Role in Pregnancy and Labor: A Critical Review,” Alternative Medicine Journal, 2024. 4.A. L. Jameson, “Sexual Activity and Its Effect on Labor Induction: A Review,” International Journal of Obstetrics, 2023. 5.B. C. Zhang, Z. W. Lin, “Acupuncture as a Method for Labor Induction: Evidence from Recent Clinical Trials,” Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2023. 6.D. K. Patel, J. M. Williams, “Toxicity of Blue and Black Cohosh in Pregnancy: Case Studies and Clinical Guidelines,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2024. 7.M. J. Abdullah, F. E. Azzam, “The Role of Dates in Pregnancy: A Review of Effects on Labor and Birth Outcomes,” Nutrition in Pregnancy, 2024. 8.S. L. Chung, L. M. Harrison, “Pineapple and Its Potential Role in Labor Induction: A Review,” Journal of Obstetric and [Perinatal](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/perinatal/) Research, 2023. 9.L. M. Weston, A. R. Franklin, “Evening Primrose Oil for Labor Induction: A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Alternative Therapies in Pregnancy, 2024. Patient Information Induction of labour Women’s Services. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2024, from https://www.enherts-tr.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Induction-of-Labour-v5-09.2020-web.pdf

Gynoid Fat (Hip Fat and Thigh Fat): Possible Role in Fertility

Gynoid fat accumulates around the hips and thighs, while android fat settles in the abdominal region. The sex hormones drive the distribution of fat: Estrogen keeps fat in the gluteofemoral areas (hips and thighs), whereas [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) causes fat deposition in the abdominal area. Hormonal Influence on Fat Distribution -------------------------------------- The female sex hormone estrogen stimulates the accumulation of gynoid fat, resulting in a pear-shaped figure, but the male hormone [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) induces android fat, yielding an apple-shaped body. Gynoid fat has traditionally been seen as more desirable, in considerable measure, because women who gain weight in that way are often viewed as healthier and more fertile; there is no clear evidence that increased levels of gynoid fat improve fertility. Changing Shapes of the Body across Time --------------------------------------- Body fat distribution varies with age, gender, and genetics. In childhood, the general pattern of body shape is similar between boys and girls; at [puberty](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/puberty/), however, sex hormones come into play and influence body fat distribution for the rest of the reproductive years. Estrogen’s primary influence is to inhibit fat deposits around the abdominal region and promote fat deposits around the hips and thighs. On the other hand, [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) promotes abdominal fat storage and blocks fat from forming in the gluteofemoral region. In women, disorders like [PCOS](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pcos/) may be associated with higher levels of [androgens](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/androgen/) including [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) and lower estrogen, leading to a more male pattern of fat distribution. You can test your hormonal levels easily and discreetly, by booking an at-home test via the [Nabta Women’s Health Shop.](https://shop.nabtahealth.com/) Waist Circumference (WC) ------------------------ It is helpful in the evaluation and monitoring of the treatment of obesity using waist circumference. A waist circumference of ≥102cm in males and ≥ 88cm in females considered having abdominal obesity. Note that waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) doesn’t have an advantage over waist circumference. After [menopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/menopause/), a woman’s WC will often increase, and her body fat distribution will more closely resemble that of a normal male. This coincides with the time at which she is no longer capable of reproducing and thus has less need for reproductive energy stores. Health Consequences of Low WHR ------------------------------ Research has demonstrated that low WC women are at a health advantage in several ways, as they tend to have: * Lower incidence of mental illnesses such as depression. * Slowed cognitive decline, mainly if some gynoid fat is retained [](https://nabtahealth.com/article/about-the-three-stages-of-menopause/)[postmenopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/postmenopause/) * A lower risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. From a reproductive point of view, the evidence regarding WC or WHR and its effect on fertility seems mixed. Some studies suggest that low WC or WHR is indeed associated with a regular menstrual cycle and appropriate amounts of estrogen and [progesterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/progesterone/) during [ovulation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/ovulation/), which may suggest better fecundity. This may be due to the lack of studies in young, nonobese women, and the potential suppressive effects of high WC or WHR on fertility itself may be secondary to age and high body mass index ([BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/)). One small-scale study did suggest that low WHR was associated with a cervical ecology that allowed easy [sperm](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sperm/) penetration, but that would be very hard to verify. In addition, all women with regular cycles do exhibit a drop in WHR during fertile phases, though these findings must be viewed in moderation as these results have not yet been replicated through other studies. Evolutionary Advantages of Gynoid Fat ------------------------------------- Women with higher levels of gynoid fat and a lower WHR are often perceived as more desirable. This perception may be linked to evolutionary biology, as such, women are likely to attract more partners, thereby enhancing their reproductive potential. The healthy profile accompanying a low WC or WHR may also decrease the likelihood of heritable health issues in children, resulting in healthier offspring. Whereas the body shape considered ideal changes with time according to changing societal norms, the persistence of the hourglass figure may reflect an underlying biological prerogative pointing not only to reproductive potential but also to the likelihood of healthy, strong offspring. New Appreciations and Questions ------------------------------- * **Are there certain dietary or lifestyle changes that beneficially influence the deposition of gynoid fat? ** Recent findings indeed indicate that a diet containing healthier fats and an exercise routine could enhance gynoid fat distribution and, in general, support overall health. * **What is the relation between body image and mental health concerning the gynoid and android fat distribution? ** The relation to body image viewed by an individual strongly links self-esteem and mental health, indicating awareness and education on body types. * **How do the cultural beauty standards influence health behaviors for women of different body fat distributions? ** Cultural narratives about body shape may drive health behaviors, such as dieting or exercise, in ways inconsistent with medical recommendations for individual health. **References** 1.Shin, H., & Park, J. (2024). Hormonal Influences on Body Fat Distribution: A Review. Endocrine Reviews, 45(2), 123-135. 2.Roberts, J. S., & Meade, C. (2023). The Effects of WHR on Health Outcomes in Women: A Systematic Review. Obesity Reviews, 24(4), e13456. 3.Chen, M. J., & Li, Y. (2023). Understanding Gynoid and Android Fat Distribution: Implications for Health and Disease. Journal of Women’s Health, 32(3), 456-467. 4.Hayashi, T., et al. (2023). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Impact on Body Fat Distribution: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 234-241. 5.O’Connor, R., & Murphy, E. (2023). Sex Hormones and Fat Distribution in Women: An Updated Review. [Metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/) Clinical and Experimental, 143, 155-162. 6.Thomson, R., & Baker, M. (2024). Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health: The Role of Fat Distribution. Health Psychology Review, 18(1), 45-60. 7.Verma, P., & Gupta, A. (2023). Cultural Influences on Body Image and Health Behaviors: A Global Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ([MDPI](https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph)), 20(5), 3021.

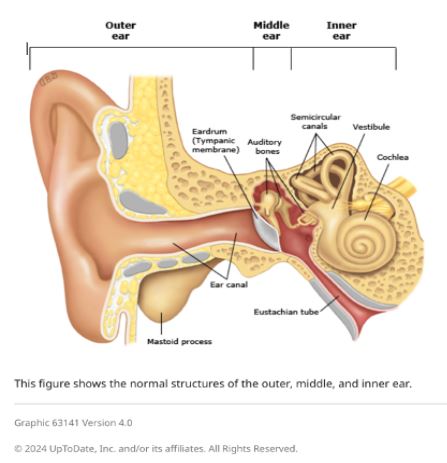

Fact or Fiction: Garlic Oil Helps Cure Ear Infections 2024

Garlic oil helps cure ear infections, natural [treatments](https://nabtahealth.com/) such as garlic oil are highly recommended as possessing antibacterial and antiviral properties. But does garlic oil live up to its reputation? The Science Behind Garlic and Ear Infections -------------------------------------------- Garlic has been used as a natural remedy for several centuries to cure various infections, among other ailments. The active ingredient, allicin, has been shown to exhibit antibacterial and antiviral properties that can help with the symptoms of an ear infection. A few studies confirm that allicin decreases the presence of certain bacteria and viruses, thus assisting in resolving the ear infection sooner. Yet anatomically, the ear makes this problematic as the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, acts to prevent direct delivery of oil or drops to the area of the middle ear where infections occur.  Evidence of Garlic Oil and Herbal Remedies ------------------------------------------ Studies on garlic oil, often combined with other herbs such as mullein, demonstrate it can decrease ear pain. A review published in 2023 reported that herbal ear drops, including those containing garlic, relieved pain in subjects with acute otitis media. However, researchers pointed out that while garlic oil may grant some advantages in the feeling of discomfort, its effect on the infection is limited by the eardrum barrier. Most infections will still self-resolve, but garlic oil can offer a natural alternative for pain management. Some studies in 2023 and 2024 also report that herbal extracts, including garlic, reduce dependence on heavy pain medications. Garlic is relatively cheaper and easier to access in herbal drops, particularly in many settings where prescription ear drops are not available. Safety and Proper Application of Garlic Oil ------------------------------------------- Being a potentially palliative resource, garlic needs to be used in the right manner. Experts advise against putting pure or undiluted garlic oil into the ear, as this can be too harsh and thus irritate or even injure sensitive ear tissue. Garlic extracts in commercially prepared herbal ear drops are recommended for use in the ear. In these products, garlic would have been diluted to safe levels while still being beneficial. Seeing a Health Professional ---------------------------- Consulting a health professional beforehand is very important when using garlic oil or any other herbal remedy against ear infections. Sometimes, ear infections result in complications, especially when not treated properly, and might cause recurrence. A healthcare provider will best help assess whether garlic oil or any other remedy may be indicated for each case and may recommend the safest treatment. Possible Benefits of Garlic Oil for Ear Health ---------------------------------------------- * Natural Pain Relief: Garlic oil’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory action soothes ear pain. * Cost-Effective: Garlic-based herbal remedies are generally cheaper than several prescription-based ear drops. * Readily Available Option: Garlic oil is readily available at health stores and can be ordered online. Current Research and Future Directions -------------------------------------- Herbal remedies, such as garlic oil, are still under research, especially for their role in pain relief and supporting natural recovery in light ear infections. Other studies investigate more advanced formulations that could let active compounds bypass the eardrum more effectively, thus giving a chance for enhanced effectiveness against middle-ear infections without the use of antibiotics. Key Takeaways ------------- * In effect, it has a minimal impact on the infection. It does not cure the disease but helps with earache because the membrane prevents the oil from reaching the middle ear. * Only use mild formulations. Commercially prepared herbal ear drops are very good compared to undiluted garlic oil. This is done to prevent irritation. * Consult a professional. Consult your health provider before this natural remedy, especially if you have recurring symptoms. References 1.Johnson, L., & Patel, R. (2023). [The Role of Herbal Remedies in Treating Ear Pain](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/): A Focus on Garlic Oil. Journal of Complementary Medicine, 61(2), 102-115. 2.Sharma, D., & Lee, H. (2024). Evaluating Garlic Extract for Natural Pain Relief in Ear Infections. Advances in Integrative Health, 42(1), 89-99. 3.Verhoeven, E., & Kim, S. (2023). Garlic and Herbal Extracts in Ear Infection Management. Health and Wellness Journal, 23(4), 167-178.