Exploring the Proposed Health Benefits of Activated Charcoal

Dr. Kate Dudek • December 13, 2022 • 5 min read

Activated charcoal is a fine black powder made from naturally occurring carbon-based materials such as coconut shells, peat, wood and coal. To activate it, the charcoal is heated to high temperatures and then injected with steam, maximising the surface area and making it more porous. The porous nature of activated charcoal helps to trap toxins and chemicals found in the gut, preventing the body from absorbing them. Activated charcoal is not absorbed, so both it and any trapped toxins are eliminated from the body in the faeces.

These toxin removal properties led to activated charcoal becoming the most frequently employed gastrointestinal decontaminant. Thus, its most well established use is as a poison antidote and a remedy for drug overdose. Unfortunately, the window of effectiveness is narrow, requiring ingestion as soon as possible after poisoning or overdose, ideally within 30 minutes.

Activated charcoal has been in use for over 150 years, however in recent years it has grown in popularity; a staple in celebrity-endorsed weight loss plans and detoxification programmes. So, is there merit in its use? Can it help with weight loss and other health issues, or is it just the latest fad?

What Does Activated Charcoal do?

The claims:

- Promotes kidney function.

- Decreases cholesterol levels.

- Reduces intestinal gases.

- Whitens teeth.

- Resolves a hangover.

Activated charcoal has been shown to benefit some patients with chronic kidney disease. It helps to reduce the number of waste products (toxins derved from urea) that would otherwise need to be filtered by the kidneys.

Unfortunately most of the work in relation to the effects of activated charcoal on cholesterol levels are from the 1980s. These studies suggest that taking 24g activated charcoal for 4 weeks can lower the levels of ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol by up to 40%, and increase the levels of ‘good’ HDL cholesterol by 8%. Another study found that the ratio of HDL/LDL cholesterol was increased from 0.13 to 0.23 over a 3 week period. However, the number of participants was small and further validation of this data is lacking.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reports that taking at least 1g activated charcoal 30 minutes before a meal and again after eating, “contributes to the reduction of excessive intestinal gas accumulation”. They failed to find definitive evidence that it reduced bloating.

The evidence in favour of using activated charcoal as a tooth whitening product is predominantly anecdotal, with those in favour claiming that it retains and absorbs particles that would otherwise stain the teeth. 96% of commercially available toothpastes that contain activated charcoal claim to whiten teeth, however, the scientific evidence is limited. One study did find that continual use of such a toothpaste resulted in effective whitening, however, other whitening ingredients performed better.

Whilst activated charcoal works well to counteract some poisons and drugs, including paracetamol, it has little effect following alcohol poisoning. Consequently, there is no evidence that it can alleviate the discomfort caused by excessive alcohol consumption and it makes a poor hangover cure.

The take home message

Medically, activated charcoal has experienced declining use in recent years, although it can still work well if implemented swiftly after an overdose of certain medications. It has few severe side effects, but can cause constipation and black stools. One major problem is that it can interfere with the absorption of certain medications, so if you are considering using it, but are on regular medication, you should consult a doctor first. Many of the suggested benefits of activated charcoal are not supported by scientific studies and, in instances where there is evidence, it is often weak and unsubstantiated.

There is no healthy weight loss benefit to taking activated charcoal and it can actually be detrimental if it hinders the absorption of other vitamins and minerals by the body. The water soluble vitamins C and B have been shown to bind to activated charcoal when it is combined with apple juice in a laboratory setting. If this also happens inside the human body, the health benefits of a diet rich in vitamin C and vitamin B could be lost.

Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and menopause.

Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you.

Sources:

- Albertson, T E, et al. “Gastrointestinal Decontamination in the Acutely Poisoned Patient.” International Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 4, 2011, p. 65., doi:10.1186/1865-1380-4-65.

- Juurlink, D N. “Activated Charcoal for Acute Overdose: a Reappraisal.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 81, no. 3, Mar. 2016, doi:10.1111/bcp.12793.

- Kadakal, Çetin, et al. “Effect Of Activated Charcoal On Water-Soluble Vitamin Content Of Apple Juice.” Journal of Food Quality, vol. 27, no. 2, 2004, pp. 171–180., doi:10.1111/j.1745-4557.2004.tb00647.x.

- Kuusisto, P, et al. “Effect of AC on Hypercholesterolaemia.” The Lancet, vol. 2, no. 8503, 16 Aug. 1986, pp. 366–367., doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90054-1.

- Neuvonen, P J, et al. “Activated Charcoal in the Treatment of Hypercholesterolaemia: Dose-Response Relationships and Comparison with Cholestyramine.” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 37, no. 3, 1989, pp. 225–230.

- EFSA. “Scientific Opinion on the Substantiation of Health Claims Related to AC and Reduction of Excessive Intestinal Gas Accumulation (ID 1938) and Reduction of Bloating (ID 1938) Pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006.” European Food Safety Journal, vol. 9, no. 4, 2011, p. 2049., efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2049.

- Vaz, V T P, et al. “Whitening Toothpaste Containing AC, Blue Covarine, Hydrogen Peroxide or Microbeads: Which One Is the Most Effective?” Journal of Applied Oral Science, vol. 27, 14 Jan. 2019, p. e20180051., doi:10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0051.

Download the Nabta App

Related Articles

9 Natural Induction Methods Examined: What Does the Evidence Say?

Towards the end of [pregnancies](https://nabtahealth.com/article/ectopic-pregnancies-why-do-they-happen/), many women try methods of natural induction. The evidence supporting various traditional methods is variable, and benefits, side effects, and notable potential health risks are present. Understanding what science says can help individuals make informed choices in consultation with a provider. Induction of Natural Labour induction Myths, Realities and Precautions ---------------------------------------------------------------------- The following section will review nine standard natural induction methods, discussing the proposed mechanism, evidence, and safety considerations. Avoid potential hazards by avoiding risky labor triggers and get advice from your [obstetrician](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/obstetrician/) before choosing any method mentioned below. Castor Oil ---------- Castor oil has been used throughout the centuries to induce labor, and studies suggest that it does so on some 58% of occasions. This oil stimulates prostaglandin release, which in turn may have the result of inducing cervical changes. Adverse effects, such as nausea and [diarrhea](https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diarrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20352241), are common, however. Castor oil should be used near the [due date](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/due-date/) and with extreme caution, given its contraindication earlier in pregnancy. Breast Stimulation ------------------ The historical and scientific backing of breast stimulation is based on the release of oxytocin to soften the [cervix](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cervix/). A study has shown that, with this method, cervical ripening may be achieved in about 37% of cases. However, excessive stimulation may cause uterine hyperstimulation, and guidance from professionals may be essential. Red Raspberry Leaf ------------------ Red raspberry leaf is generally taken as a tea and is thought to enhance blood flow to the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/) and stimulate [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/). Traditional use, however, is tempered by a relative lack of scientific research regarding its effectiveness. Animal studies have suggested possible adverse side effects, and no human data are available that supports a correlation with successful induction of labor. Sex --- Sex is most commonly advised as a natural induction method based on the principle that sex introduces [prostaglandins](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/prostaglandins/) and oxytocin, and orgasm induces uterine [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/). The few studies in the literature report no significant effect on labor timing. Generally safe for women when pregnancy is otherwise low-risk but may not speed labor. Acupuncture ----------- Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese practice that has been done to stimulate labor through the induction of hormonal responses. However, some studies show its effectiveness in improving cervical ripening but not necessarily inducing active labor. An experienced practitioner would appropriately consult its safe application during pregnancy. Blue and Black Cohosh --------------------- Native American groups traditionally utilize blue and black cohosh plants for gynecological use. These plants are highly discouraged nowadays from inducing labor because of the risk of toxicity they may bring. Although they establish substantial [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/), they have been observed to sometimes cause extreme complications-possibly congenital disabilities and heart problems in newborns Dates ----- Some cultural beliefs view dates as helping induce labor by stimulating the release of oxytocin. They do not help stimulate uterine [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/) to start labor, but clinical research does support that dates support cervical [dilation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/dilation/) and reduce the need for medical inductions during labor. They also support less hemorrhaging post-delivery when consumed later in pregnancy. Pineapple --------- Something in pineapple called bromelain is an [enzyme](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/enzyme/) that is supposed to stimulate [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/) of the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/). Animal tissue studies have determined it would only work if applied directly to the tissue, so it’s doubtful this is a natural method for inducing labor. Evening Primrose Oil -------------------- Evening Primrose Oil, taken almost exclusively in capsule form, is another common naturopathic remedy to ripen the [cervix](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cervix/). Still, studies are very few and indicate a greater risk of labor complications, such as intervention during delivery, and it is not recommended very often. Safety and Consultation ----------------------- Many of these methods are extremely popular; however, most are unsupported by scientific data. Any method should be discussed with a healthcare provider because all may be contraindicated depending on gestational age, maternal health, and pregnancy risk levels. Try going for a walk, have a warm bath and relax while you’re waiting for your baby. “Optimal fetal positioning,” can help baby to come into a better position to support labor. You can try sitting upright and leaning forward by sitting on a chair backward. Conclusion ---------- Natural methods of inducing labor vary widely in efficacy and safety. Practices like breast stimulation and dates confer some benefits, while others, such as those involving castor oil and blue cohosh, carry risks. Based on the available evidence, decisions about labor induction through healthcare providers are usually the safest. You can track your menstrual cycle and get [personalised support by using the Nabta app](https://nabtahealth.com/nabta-app/). Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you. Sources : 1.S. M. Okun, R. A. Lydon-Rochelle, and L. L. Sampson, “Effect of Castor Oil on Induction of Labor: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 2023. 2.T. K. Ford, H. H. Snell, “Effectiveness of Breast Stimulation for Cervical Ripening and Labor Induction: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2023. 3.R. E. Smith, D. M. Wilson, “Red Raspberry Leaf and Its Role in Pregnancy and Labor: A Critical Review,” Alternative Medicine Journal, 2024. 4.A. L. Jameson, “Sexual Activity and Its Effect on Labor Induction: A Review,” International Journal of Obstetrics, 2023. 5.B. C. Zhang, Z. W. Lin, “Acupuncture as a Method for Labor Induction: Evidence from Recent Clinical Trials,” Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2023. 6.D. K. Patel, J. M. Williams, “Toxicity of Blue and Black Cohosh in Pregnancy: Case Studies and Clinical Guidelines,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2024. 7.M. J. Abdullah, F. E. Azzam, “The Role of Dates in Pregnancy: A Review of Effects on Labor and Birth Outcomes,” Nutrition in Pregnancy, 2024. 8.S. L. Chung, L. M. Harrison, “Pineapple and Its Potential Role in Labor Induction: A Review,” Journal of Obstetric and [Perinatal](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/perinatal/) Research, 2023. 9.L. M. Weston, A. R. Franklin, “Evening Primrose Oil for Labor Induction: A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Alternative Therapies in Pregnancy, 2024. Patient Information Induction of labour Women’s Services. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2024, from https://www.enherts-tr.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Induction-of-Labour-v5-09.2020-web.pdf

Gynoid Fat (Hip Fat and Thigh Fat): Possible Role in Fertility

Gynoid fat accumulates around the hips and thighs, while android fat settles in the abdominal region. The sex hormones drive the distribution of fat: Estrogen keeps fat in the gluteofemoral areas (hips and thighs), whereas [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) causes fat deposition in the abdominal area. Hormonal Influence on Fat Distribution -------------------------------------- The female sex hormone estrogen stimulates the accumulation of gynoid fat, resulting in a pear-shaped figure, but the male hormone [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) induces android fat, yielding an apple-shaped body. Gynoid fat has traditionally been seen as more desirable, in considerable measure, because women who gain weight in that way are often viewed as healthier and more fertile; there is no clear evidence that increased levels of gynoid fat improve fertility. Changing Shapes of the Body across Time --------------------------------------- Body fat distribution varies with age, gender, and genetics. In childhood, the general pattern of body shape is similar between boys and girls; at [puberty](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/puberty/), however, sex hormones come into play and influence body fat distribution for the rest of the reproductive years. Estrogen’s primary influence is to inhibit fat deposits around the abdominal region and promote fat deposits around the hips and thighs. On the other hand, [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) promotes abdominal fat storage and blocks fat from forming in the gluteofemoral region. In women, disorders like [PCOS](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pcos/) may be associated with higher levels of [androgens](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/androgen/) including [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) and lower estrogen, leading to a more male pattern of fat distribution. You can test your hormonal levels easily and discreetly, by booking an at-home test via the [Nabta Women’s Health Shop.](https://shop.nabtahealth.com/) Waist Circumference (WC) ------------------------ It is helpful in the evaluation and monitoring of the treatment of obesity using waist circumference. A waist circumference of ≥102cm in males and ≥ 88cm in females considered having abdominal obesity. Note that waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) doesn’t have an advantage over waist circumference. After [menopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/menopause/), a woman’s WC will often increase, and her body fat distribution will more closely resemble that of a normal male. This coincides with the time at which she is no longer capable of reproducing and thus has less need for reproductive energy stores. Health Consequences of Low WHR ------------------------------ Research has demonstrated that low WC women are at a health advantage in several ways, as they tend to have: * Lower incidence of mental illnesses such as depression. * Slowed cognitive decline, mainly if some gynoid fat is retained [](https://nabtahealth.com/article/about-the-three-stages-of-menopause/)[postmenopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/postmenopause/) * A lower risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. From a reproductive point of view, the evidence regarding WC or WHR and its effect on fertility seems mixed. Some studies suggest that low WC or WHR is indeed associated with a regular menstrual cycle and appropriate amounts of estrogen and [progesterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/progesterone/) during [ovulation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/ovulation/), which may suggest better fecundity. This may be due to the lack of studies in young, nonobese women, and the potential suppressive effects of high WC or WHR on fertility itself may be secondary to age and high body mass index ([BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/)). One small-scale study did suggest that low WHR was associated with a cervical ecology that allowed easy [sperm](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sperm/) penetration, but that would be very hard to verify. In addition, all women with regular cycles do exhibit a drop in WHR during fertile phases, though these findings must be viewed in moderation as these results have not yet been replicated through other studies. Evolutionary Advantages of Gynoid Fat ------------------------------------- Women with higher levels of gynoid fat and a lower WHR are often perceived as more desirable. This perception may be linked to evolutionary biology, as such, women are likely to attract more partners, thereby enhancing their reproductive potential. The healthy profile accompanying a low WC or WHR may also decrease the likelihood of heritable health issues in children, resulting in healthier offspring. Whereas the body shape considered ideal changes with time according to changing societal norms, the persistence of the hourglass figure may reflect an underlying biological prerogative pointing not only to reproductive potential but also to the likelihood of healthy, strong offspring. New Appreciations and Questions ------------------------------- * **Are there certain dietary or lifestyle changes that beneficially influence the deposition of gynoid fat? ** Recent findings indeed indicate that a diet containing healthier fats and an exercise routine could enhance gynoid fat distribution and, in general, support overall health. * **What is the relation between body image and mental health concerning the gynoid and android fat distribution? ** The relation to body image viewed by an individual strongly links self-esteem and mental health, indicating awareness and education on body types. * **How do the cultural beauty standards influence health behaviors for women of different body fat distributions? ** Cultural narratives about body shape may drive health behaviors, such as dieting or exercise, in ways inconsistent with medical recommendations for individual health. **References** 1.Shin, H., & Park, J. (2024). Hormonal Influences on Body Fat Distribution: A Review. Endocrine Reviews, 45(2), 123-135. 2.Roberts, J. S., & Meade, C. (2023). The Effects of WHR on Health Outcomes in Women: A Systematic Review. Obesity Reviews, 24(4), e13456. 3.Chen, M. J., & Li, Y. (2023). Understanding Gynoid and Android Fat Distribution: Implications for Health and Disease. Journal of Women’s Health, 32(3), 456-467. 4.Hayashi, T., et al. (2023). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Impact on Body Fat Distribution: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 234-241. 5.O’Connor, R., & Murphy, E. (2023). Sex Hormones and Fat Distribution in Women: An Updated Review. [Metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/) Clinical and Experimental, 143, 155-162. 6.Thomson, R., & Baker, M. (2024). Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health: The Role of Fat Distribution. Health Psychology Review, 18(1), 45-60. 7.Verma, P., & Gupta, A. (2023). Cultural Influences on Body Image and Health Behaviors: A Global Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ([MDPI](https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph)), 20(5), 3021.

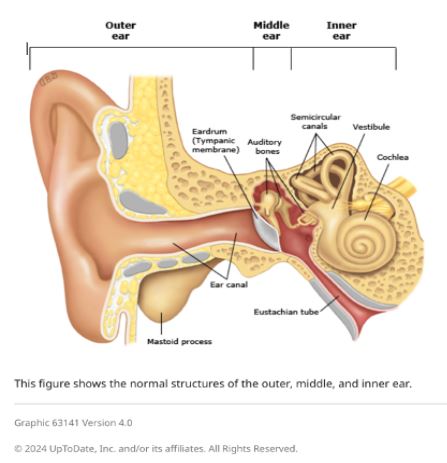

Fact or Fiction: Garlic Oil Helps Cure Ear Infections 2024

Garlic oil helps cure ear infections, natural [treatments](https://nabtahealth.com/) such as garlic oil are highly recommended as possessing antibacterial and antiviral properties. But does garlic oil live up to its reputation? The Science Behind Garlic and Ear Infections -------------------------------------------- Garlic has been used as a natural remedy for several centuries to cure various infections, among other ailments. The active ingredient, allicin, has been shown to exhibit antibacterial and antiviral properties that can help with the symptoms of an ear infection. A few studies confirm that allicin decreases the presence of certain bacteria and viruses, thus assisting in resolving the ear infection sooner. Yet anatomically, the ear makes this problematic as the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, acts to prevent direct delivery of oil or drops to the area of the middle ear where infections occur.  Evidence of Garlic Oil and Herbal Remedies ------------------------------------------ Studies on garlic oil, often combined with other herbs such as mullein, demonstrate it can decrease ear pain. A review published in 2023 reported that herbal ear drops, including those containing garlic, relieved pain in subjects with acute otitis media. However, researchers pointed out that while garlic oil may grant some advantages in the feeling of discomfort, its effect on the infection is limited by the eardrum barrier. Most infections will still self-resolve, but garlic oil can offer a natural alternative for pain management. Some studies in 2023 and 2024 also report that herbal extracts, including garlic, reduce dependence on heavy pain medications. Garlic is relatively cheaper and easier to access in herbal drops, particularly in many settings where prescription ear drops are not available. Safety and Proper Application of Garlic Oil ------------------------------------------- Being a potentially palliative resource, garlic needs to be used in the right manner. Experts advise against putting pure or undiluted garlic oil into the ear, as this can be too harsh and thus irritate or even injure sensitive ear tissue. Garlic extracts in commercially prepared herbal ear drops are recommended for use in the ear. In these products, garlic would have been diluted to safe levels while still being beneficial. Seeing a Health Professional ---------------------------- Consulting a health professional beforehand is very important when using garlic oil or any other herbal remedy against ear infections. Sometimes, ear infections result in complications, especially when not treated properly, and might cause recurrence. A healthcare provider will best help assess whether garlic oil or any other remedy may be indicated for each case and may recommend the safest treatment. Possible Benefits of Garlic Oil for Ear Health ---------------------------------------------- * Natural Pain Relief: Garlic oil’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory action soothes ear pain. * Cost-Effective: Garlic-based herbal remedies are generally cheaper than several prescription-based ear drops. * Readily Available Option: Garlic oil is readily available at health stores and can be ordered online. Current Research and Future Directions -------------------------------------- Herbal remedies, such as garlic oil, are still under research, especially for their role in pain relief and supporting natural recovery in light ear infections. Other studies investigate more advanced formulations that could let active compounds bypass the eardrum more effectively, thus giving a chance for enhanced effectiveness against middle-ear infections without the use of antibiotics. Key Takeaways ------------- * In effect, it has a minimal impact on the infection. It does not cure the disease but helps with earache because the membrane prevents the oil from reaching the middle ear. * Only use mild formulations. Commercially prepared herbal ear drops are very good compared to undiluted garlic oil. This is done to prevent irritation. * Consult a professional. Consult your health provider before this natural remedy, especially if you have recurring symptoms. References 1.Johnson, L., & Patel, R. (2023). [The Role of Herbal Remedies in Treating Ear Pain](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/): A Focus on Garlic Oil. Journal of Complementary Medicine, 61(2), 102-115. 2.Sharma, D., & Lee, H. (2024). Evaluating Garlic Extract for Natural Pain Relief in Ear Infections. Advances in Integrative Health, 42(1), 89-99. 3.Verhoeven, E., & Kim, S. (2023). Garlic and Herbal Extracts in Ear Infection Management. Health and Wellness Journal, 23(4), 167-178.