How Does Obesity Affect Your Fertility?

Nabta Editorial Team • September 28, 2018 • 5 min read

Obesity affects the quality and frequency of your ovulation. Obesity can affect the hormonal balance that regulates your menstrual cycle, which can in turn cause more cycles to be anovulatory (the ovary doesn’t release an egg in such cycles).

In addition, even when obese women do ovulate, the quality of the eggs is reduced.

Both of the above factors contribute to lower fertility in obese women. Losing even 5 percent of your body weight can increase your chances of getting pregnant.

Source: Williams Gynaecology, 3rd Edition

Download the Nabta App

Related Articles

Gynoid Fat (Hip Fat and Thigh Fat): Possible Role in Fertility

Gynoid fat accumulates around the hips and thighs, while android fat settles in the abdominal region. The sex hormones drive the distribution of fat: Estrogen keeps fat in the gluteofemoral areas (hips and thighs), whereas [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) causes fat deposition in the abdominal area. Hormonal Influence on Fat Distribution -------------------------------------- The female sex hormone estrogen stimulates the accumulation of gynoid fat, resulting in a pear-shaped figure, but the male hormone [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) induces android fat, yielding an apple-shaped body. Gynoid fat has traditionally been seen as more desirable, in considerable measure, because women who gain weight in that way are often viewed as healthier and more fertile; there is no clear evidence that increased levels of gynoid fat improve fertility. Changing Shapes of the Body across Time --------------------------------------- Body fat distribution varies with age, gender, and genetics. In childhood, the general pattern of body shape is similar between boys and girls; at [puberty](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/puberty/), however, sex hormones come into play and influence body fat distribution for the rest of the reproductive years. Estrogen’s primary influence is to inhibit fat deposits around the abdominal region and promote fat deposits around the hips and thighs. On the other hand, [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) promotes abdominal fat storage and blocks fat from forming in the gluteofemoral region. In women, disorders like [PCOS](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pcos/) may be associated with higher levels of [androgens](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/androgen/) including [testosterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/testosterone/) and lower estrogen, leading to a more male pattern of fat distribution. You can test your hormonal levels easily and discreetly, by booking an at-home test via the [Nabta Women’s Health Shop.](https://shop.nabtahealth.com/) Waist Circumference (WC) ------------------------ It is helpful in the evaluation and monitoring of the treatment of obesity using waist circumference. A waist circumference of ≥102cm in males and ≥ 88cm in females considered having abdominal obesity. Note that waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) doesn’t have an advantage over waist circumference. After [menopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/menopause/), a woman’s WC will often increase, and her body fat distribution will more closely resemble that of a normal male. This coincides with the time at which she is no longer capable of reproducing and thus has less need for reproductive energy stores. Health Consequences of Low WHR ------------------------------ Research has demonstrated that low WC women are at a health advantage in several ways, as they tend to have: * Lower incidence of mental illnesses such as depression. * Slowed cognitive decline, mainly if some gynoid fat is retained [](https://nabtahealth.com/article/about-the-three-stages-of-menopause/)[postmenopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/postmenopause/) * A lower risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. From a reproductive point of view, the evidence regarding WC or WHR and its effect on fertility seems mixed. Some studies suggest that low WC or WHR is indeed associated with a regular menstrual cycle and appropriate amounts of estrogen and [progesterone](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/progesterone/) during [ovulation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/ovulation/), which may suggest better fecundity. This may be due to the lack of studies in young, nonobese women, and the potential suppressive effects of high WC or WHR on fertility itself may be secondary to age and high body mass index ([BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/)). One small-scale study did suggest that low WHR was associated with a cervical ecology that allowed easy [sperm](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sperm/) penetration, but that would be very hard to verify. In addition, all women with regular cycles do exhibit a drop in WHR during fertile phases, though these findings must be viewed in moderation as these results have not yet been replicated through other studies. Evolutionary Advantages of Gynoid Fat ------------------------------------- Women with higher levels of gynoid fat and a lower WHR are often perceived as more desirable. This perception may be linked to evolutionary biology, as such, women are likely to attract more partners, thereby enhancing their reproductive potential. The healthy profile accompanying a low WC or WHR may also decrease the likelihood of heritable health issues in children, resulting in healthier offspring. Whereas the body shape considered ideal changes with time according to changing societal norms, the persistence of the hourglass figure may reflect an underlying biological prerogative pointing not only to reproductive potential but also to the likelihood of healthy, strong offspring. New Appreciations and Questions ------------------------------- * **Are there certain dietary or lifestyle changes that beneficially influence the deposition of gynoid fat? ** Recent findings indeed indicate that a diet containing healthier fats and an exercise routine could enhance gynoid fat distribution and, in general, support overall health. * **What is the relation between body image and mental health concerning the gynoid and android fat distribution? ** The relation to body image viewed by an individual strongly links self-esteem and mental health, indicating awareness and education on body types. * **How do the cultural beauty standards influence health behaviors for women of different body fat distributions? ** Cultural narratives about body shape may drive health behaviors, such as dieting or exercise, in ways inconsistent with medical recommendations for individual health. **References** 1.Shin, H., & Park, J. (2024). Hormonal Influences on Body Fat Distribution: A Review. Endocrine Reviews, 45(2), 123-135. 2.Roberts, J. S., & Meade, C. (2023). The Effects of WHR on Health Outcomes in Women: A Systematic Review. Obesity Reviews, 24(4), e13456. 3.Chen, M. J., & Li, Y. (2023). Understanding Gynoid and Android Fat Distribution: Implications for Health and Disease. Journal of Women’s Health, 32(3), 456-467. 4.Hayashi, T., et al. (2023). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Impact on Body Fat Distribution: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 234-241. 5.O’Connor, R., & Murphy, E. (2023). Sex Hormones and Fat Distribution in Women: An Updated Review. [Metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/) Clinical and Experimental, 143, 155-162. 6.Thomson, R., & Baker, M. (2024). Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health: The Role of Fat Distribution. Health Psychology Review, 18(1), 45-60. 7.Verma, P., & Gupta, A. (2023). Cultural Influences on Body Image and Health Behaviors: A Global Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ([MDPI](https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph)), 20(5), 3021.

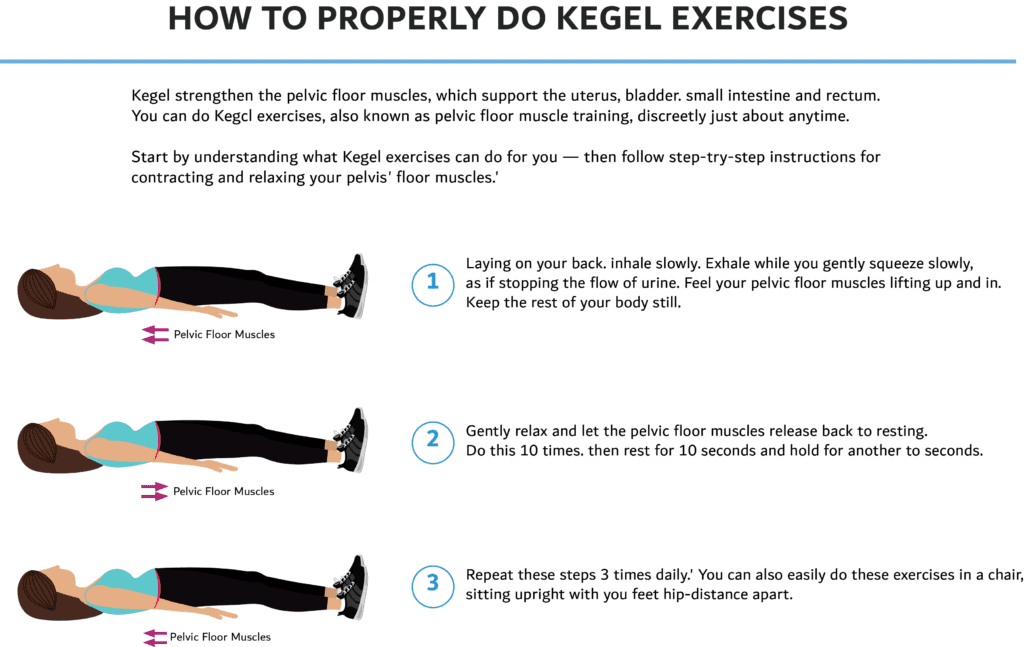

The Benefits of Postnatal Physiotherapy

Postnatal exercise can help you recover after childbirth, make you stronger and improve your mood. Even if you’re tired and not feeling motivated, there’s plenty you can do to get your body moving. But no 2 pregnancies are the same. How soon you’re ready to start exercising depends on your individual circumstances. You should always check with a health professional first. When you feel ready to exercise, it’s very important to not overdo it. [Your body](https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/what-happens-to-your-body-in-childbirth) has been through some big changes. You will need time to recover, even if you’re feeling great after having your baby. **Why should I do pelvic floor exercises after birth?** Pelvic floor exercises are important at all stages of life to prevent bladder and bowel problems, such as incontinence and prolapse, and improve sexual function. Your [pelvic floor](https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/anatomy-of-pregnancy-and-birth-perineum-pelvic-floor) is a group of muscles which support your bladder, [](https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/anatomy-of-pregnancy-and-birth-uterus)[uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/) and bowel. These muscles form a ‘sling’ which attaches to your pubic bone at the front and your tailbone at the back. Your urethra, [vagina](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/vagina/) and anus, all pass through the pelvic floor. In pregnancy, hormonal changes cause your muscles to soften and stretch more easily. These changes, along with the weight of your growing baby, put extra strain on the pelvic floor. Labour and birth can also weaken your pelvic muscles. This can increase the chance of suffering from [bladder or bowel problems](https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/bladder-and-bowel-problems-during-pregnancy) during pregnancy and after birth. Gentle exercise to restore your pelvic health is the best way to begin and you can gradually increase the intensity [](https://nabtahealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Kegel-Exersices-PNG-1024x647-1.png) **What type of exercises can I do?** Do More: 1. Gentle exercise such as walking can be done as soon as you feel comfortable after giving birth 2. Start with easy exercises and gentle stretches and slowly build up to harder ones 3. Other safe exercises include swimming (once bleeding has stopped), yoga, pilates, low impact aerobics and cycling Avoid: 1. Any high intensity exercises or sports that require rapid direction changes 2. Stretching and twisting too vigorously to prevent injury 3. Heavy weights, sit ups, crunches and planks for 3 months #### Goals of a well designed Postpartum Exercise program 1. Rest and recover 2. Maintain good posture and alignment 3. Rehabilitate the pelvic floor muscles 4. Increase strength especially in the core muscles At Nabta Health Clinic, we have specialized exercise packages which include pelvic floor rehabilitation and pilates exercise program for pregnancy and the postnatal period to help you in your well being and recovery. Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and [](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary)[menopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/menopause/). You can [email us](/cdn-cgi/l/email-protection#235a424f4f42634d424157424b46424f574b0d404c4e) or call us at **+971 4 3946122** for more information

Causes of Female Infertility – Autoimmune and Immune-Mediated Disorders

Autoimmune diseases cause the body’s own immune system to generate auto-antibodies that attack and destroy healthy body tissue by mistake. The most common autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disease and [lupus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/lupus/). Many are associated with increased risk of miscarriages and [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/). The reasons for this are not fully understood and differ between diseases, but are thought to be due to the altered immune response causing [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) of the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/) and [placenta](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/placenta/). Medications commonly prescribed for autoimmune diseases can also affect reproductive function. Conditions that are known to impact fertility, such as premature ovarian insufficiency ([POI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/poi/)), [](https://nabtahealth.com/what-is-endometriosis/)[endometriosis](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/endometriosis/) and [polycystic ovary syndrome](https://nabtahealth.com/what-is-pcos/) ([PCOS](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pcos/)) are thought to have an autoimmune component. An underlying autoimmune disease (most commonly of the thyroid and adrenal glands) has been identified in approximately 20% of patients with [POI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/poi/) and autoimmune thyroiditis has been reported in 18-40% of [PCOS](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pcos/) women, although this varies by ethnicity. Furthermore, it is hypothesised that in the 20% or more cases of idiopathic [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/), where no direct cause can be identified, inflammatory processes may play a role. #### Thyroid Disease Autoimmune thyroid disease is a common condition in women of childbearing age affecting 5-15% and can [lead](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/lead/) to either an overactive (Graves’ disease, [hyperthyroidism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hyperthyroidism/)) or underactive (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, [hypothyroidism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hypothyroidism/)) thyroid. Women with thyroid disease often experience menstrual cycle irregularities, so may struggle to conceive. #### [Lupus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/lupus/) Systemic [Lupus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/lupus/) Erythematosus (SLE) is a long-term autoimmune disease causing [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) of the joints, skin and other organs. SLE affects approximately 1 in 2000 women of childbearing age and diagnosis of the condition seems to correlate with a reduction in pregnancy rates. Women with SLE frequently exhibit [irregular periods](https://nabtahealth.com/why-are-my-periods-irregular/). This might be due to their medication, but there is also evidence of disease-specific effects. Women with SLE are immunocompromised and therefore at increased risk of [infection-induced](https://nabtahealth.com/causes-of-female-infertility-infection) [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/). There is a psychosocial element, as women who are diagnosed with SLE are at increased risk of stress, depression and reduced libido, all of which can make falling pregnant more difficult. One of the most established links between SLE and [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) relates to the [cytotoxic](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cytotoxic/) drugs used to treat the condition, for example, cyclophosphamide. Taken for prolonged periods, these drugs can cause ovarian failure. #### [Celiac Disease](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/celiac-disease/) Around 1% of women in developed countries have the autoimmune condition [celiac disease](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/celiac-disease/), where the ingestion of gluten leads to damage in the small intestine. They are at increased risk of [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) and recurrent [miscarriages](https://nabtahealth.com/pregnancy-after-miscarriage/). This is likely to be due to nutritional deficiencies in their diet. Thus, women with the condition may want to consult a nutritionist prior to attempting to start a family. #### Auto-antibodies The production of [autoantibodies](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/autoantibodies/) is central to autoimmune disease. One in five infertile couples are diagnosed with unexplained [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) (UI) in which they are unable to conceive with no obvious cause. [Autoantibodies](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/autoantibodies/) have been found to account for some cases of UI, examples include: * Anti-[sperm](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sperm/) antibodies ([ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/)) * Antibodies against the [thyroid gland](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/thyroid-gland/), or cellular components such as the nuclear membrane or the cell membrane (phospholipid) * Antiovarian antibodies. Anti-[sperm](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sperm/) antibodies ([ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/)) have been detected in the [cervical discharge](https://nabtahealth.com/cervical-discharge-through-the-menstrual-cycle/) of infertile women, as well as in the seminal fluid of their male partner. [ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/) bind to [](https://nabtahealth.com/everything-you-need-to-know-about-sperm/)[sperm](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sperm/) cells, causing them to stick together (agglutinate) resulting in [reduced movement](https://nabtahealth.com/low-sperm-motility-asthenozoospermia/) and, in many cases, reduced cervical penetration and inhibition of [implantation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/implantation/). However, further research is required on determining exactly how [ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/) affect fertility, as [ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/) have also been found in the cervical secretions of fertile women. The majority of studies assessing the relationship between [ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/) and [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) are old and have used outdated technologies which may result in false-positive results due to cross reactivity with other antibodies. The evidence of the effects of antibodies against thyroid, or cellular components such as the nuclear membrane or phospholipid and antiovarian antibodies on fertility, like [ASAs](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/asas/) is conflicted and requires further research. Furthermore, how antibodies can cause [infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) is not fully understood, and all studies suggesting a link are more about association with [autoantibodies](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/autoantibodies/) rather than a cause. Anti-[oocyte](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/oocyte/) antibodies also exist, but these seem to be a lot less common.Anti-ovarian antibodies have been detected in women with [](https://nabtahealth.com/causes-of-female-infertility-failure-to-ovulate)[POI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/poi/). They are associated with anti-follicle-stimulating hormone ([FSH](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/fsh/)) antibodies. [FSH](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/fsh/) is involved in regulating ovarian function. [Causes of Female](https://nabtahealth.com/causes-of-female-infertility-infection) [Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) – Infection ([PID](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pid/) and [HPV](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hpv/)) [Causes of Female](https://nabtahealth.com/causes-of-female-infertility-environmental-lifestyle-factors) [Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) – Environmental/Lifestyle Factors Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and [menopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/menopause/). Get in [touch](/cdn-cgi/l/email-protection#671e060b0b062709060513060f02060b130f4904080a) if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you. **Sources:** * Brazdova, A, et al. “Immune Aspects of Female [Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/).” International Journal of Fertility & Sterility , vol. 10, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1–10. * Domniz, N and Meirow, D, “Premature ovarian insufficiency and autoimmune diseases” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol 60, Oct 2019, pp 42-55. doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.07.008. * Hickman, R A, and C Gordon. “Causes and Management of [Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) in Systemic [Lupus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/lupus/) Erythematosus .” Rheumatology, vol. 50, no. 9, Sept. 2011, pp. 1551–1558., doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker105. * Khizroeva, J et al, “[Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) in women with systemic autoimmune diseases” Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & [Metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/), vol 33, Dec 2019, doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2019.101369. * Kim, N Y et al. “Thyroid autoimmunity and its association with cellular and humoral immunity in women with reproductive failures.” American Journal of reproductive immunology, vol. 65, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 78-87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00911.x. * Lebovic and Naz, “Premature ovarian failure: Think ‘autoimmune disorder’”, Sexuality, Reproduction & [Menopause](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/menopause/), vol. 2, no. 4, Dec 2004, pp.230-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sram.2004.11.010. * McCulloch, F. “Natural Treatments for Autoimmune [Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/) Concerns.” American College for Advancement in Medicine, 29 Jan. 2014, [www.acam.org/blogpost/1092863/179527/Natural-Treatments-for-Autoimmune-](http://www.acam.org/blogpost/1092863/179527/Natural-Treatments-for-Autoimmune-Infertility-Concerns)[Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/)\-Concerns. * Romitti, M et al. “Association between [PCOS](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/pcos/) and autoimmune thyroid disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Endocrine connections, vol 7, no. 11, Oct 2018, pp 1158-1167. doi: 10.1530/EC-18-0309. * Shigesi, N et al, “The association between [endometriosis](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/endometriosis/) and autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 25, no. 4, Jul 2019, pp 486-503. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz014. * “What Are Some Possible Causes of Female [Infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/)? .” National Institutes of Health, [www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/](http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/infertility/conditioninfo/causes/causes-female)[infertility](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/infertility/)/conditioninfo/causes/causes-female.