My Newborn has Been Diagnosed with a Deficiency in G6PD: What Does This Mean?

Dr. Kate Dudek • October 30, 2019 • 5 min read

Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency is one of the most common enzyme deficiencies worldwide, affecting up to 400 million people globally. So, what is it; who is at most risk; what are the symptoms and how will it affect your baby as he grows?

What causes a deficiency in G6PD?

There are thought to be over 400 mutations that can result in a deficiency of G6PD. Different gene mutations cause differing levels of enzyme deficiency, however, as a total deficiency would be incompatible with life, everyone retains at least some enzymatic activity. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has grouped the different gene variants into classes depending on the severity of the mutation:

- Class I – severe. Chronic haemolysis in the absence of any trigger.

- Class II – severe. Enzyme activity <10%. Intermittent haemolysis.

- Class III – moderate. Enzyme activity 10-60%. Haemolysis occurs following exposure to stressor.

- Class IV – mild to no enzyme deficiency. Enzyme activity 60-150%.

- Class V – no deficiency. Enzyme activity >150%.

Class IV and V are very rare; class I is uncommon, and less likely to be population-specific. Class II and III alter in prevalence depending on where in the world you live. Those who live in Africa, Asia, certain parts of the Mediterranean and the Middle East are much more likely to have a deficiency in G6PD. In some high risk populations, between 5 and 30% of people are affected. The reasons for the regional differences are not fully understood, however, prevalence does correlate strongly with the geographical distribution of malaria. It is even thought that those who carry the defect are at reduced risk of malaria infection.

G6PD mutations are x-linked, which means that males are more likely to display phenotypic symptoms of the condition. This is because men only have one X chromosome; females have two X chromosomes, so will often have a more mild form, or be a carrier of the condition. It is very rare for females to carry a mutation on both of their X chromosomes and this would normally co-exist with an additional immune condition.

What puts my child at increased risk?

As well as geographical variation and gender, children with a family history of anaemia, jaundice, splenomegaly or cholelithiasis should be considered at greater risk of having a G6PD deficiency. Having a pronounced haemolytic reaction to a known stressor will probably also prompt a doctor into considering this diagnosis.

What does a deficiency mean?

The enzyme G6PD, found in all of the body’s cells, is involved in the production of another enzyme, NADPH, which has a protective role throughout the body. It protects the cells of the body from oxidative damage. A reduction in G6PD activity means that less NADPH is produced, which means that the cells that this enzyme would normally protect are more susceptible to damage. The body is able to compensate for G6PD deficiency in most cells, however, the red blood cells are particularly vulnerable to damage and destruction.

Red blood cells transport oxygen from the lungs to the tissues of the body. If the red blood cells are destroyed faster than the body can replace them, haemoglobin is released into the blood. The medical name for this condition is haemolysis.

Many people with a deficiency in G6PD remain asymptomatic. In fact, in certain parts of the world people may be unaware that they have a deficiency. The gene mutation in isolation is insufficient to cause haemolysis and an acute episode will only occur with exposure to a particular trigger, or stressor. In parts of the world where G6PD deficiency is less common, such as the USA and the UK, testing for mutations in this gene does not form a part of the routine newborn screening test. However, the WHO has recommended it is incorporated into the standard screening assessment for babies who are born into populations where the prevalence is 3-5%. The Middle East and Africa fall into this category.

How is G6PD deficiency treated?

There is no cure for a deficiency in G6PD, but awareness is important, so that the stressors which can induce a haemolytic event can be avoided. There are three main stressors that can have a detrimental effect on people with a deficiency in G6PD:

- Infection. This is the most common cause of acute haemolysis. The infections that are most likely to trigger acute haemolysis include salmonella, Escherichia coli, streptococci, viral hepatitis, and influenza A. The mechanism is unclear, but thought to be due, in part, to the infectious agents, causing a build-up of leukocytes, which trigger oxidative stress.

- Oxidative drugs. There is a wide spectrum of drugs that can trigger haemolysis in those with G6PD deficiency; these include, antimalarials, analgesics, antipyretics and antibacterials. There is some confusion however, as to whether, in some cases, the haemolysis is triggered by the drug, or by the underlying infection for which the drug is prescribed. Following ingestion of a stressor drug, haemolysis typically occurs after 24-72 hours. It will usually resolve itself within 4 – 7 days. An important factor to bear in mind if your child has been diagnosed with G6PD deficiency is that oxidative drugs can be transmitted through the breast milk, potentially triggering acute haemolysis in vulnerable infants. As such, it is worth discussing the risk with your doctor, prior to taking any medications.

- Fava beans. Favism is a reaction to fava beans, initially thought to be an allergic reaction, but now known to be another stressor in cases of G6PD deficiency. There are two chemicals found in these beans, vicine and convicine, which are known to cause oxidative stress. Not all people with G6PD deficiency will react to fava beans, however, young children are particularly vulnerable. The effects are also usually more severe in children. Initial symptoms may include an increased temperature, irritability and lethargy; progressing to nausea, abdominal discomfort, darker urine, pale skin and jaundice. In very severe cases the child may become tachycardic.

A splenectomy will rarely be recommended for G6PD deficiency. Folic acid and iron supplements may help during haemolytic events. Fortunately most cases of acute haemolysis are self-limiting and short-lived.

In rare cases a blood transfusion may be required, however, this will usually only be necessary in those with chronic haemolysis. In the chronic condition, no stressor is required and haemolysis occurs during normal red blood cell metabolism. It is important to avoid complications in cases of chronic haemolysis as the condition can lead to hypovolemic shock and acute renal failure.

People who have a deficiency in G6PD are predisposed to the development of sepsis, so symptoms should be monitored and, as far as possible, stressors should be avoided.

Neonatal Hyperbilirubinaemia

Male babies with a mutation in the G6PD gene are twice as likely to experience neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia. This occurs when there is an excess of bilirubin in the blood. It is unclear why the bilirubin accumulates, but likely to be caused, at least in part, by impaired clearance by the liver. babies who are affected may require phototherapy or, in severe cases, transfusion.

Excess bilirubin in the blood can cause jaundice, which is one of the most common conditions requiring medical attention in newborns. It causes a yellowing of the skin and is treatable but requires rapid medical attention because in rare cases it can cause neurological issues. This happens when there is a toxic build-up of bilirubin in the brain. Warning signs to be aware of include a lack of energy, poor feeding, vomiting and fever.

Conclusion

The main thing to remember if your newborn is diagnosed with a deficiency in G6PD is that the majority of people remain clinically asymptomatic throughout life. Severe deficiencies are rare and even moderate deficiencies will only cause a physiological response with additional stressor exposure. Awareness is key, as knowing that there are specific stressors means that these can be avoided, reducing the likelihood of haemolytic episodes.

Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and menopause.

Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you.

Sources:

- Frank, J E. “Diagnosis and Management of G6PD Deficiency.” American Family Physician, vol. 72, no. 7, 1 Oct. 2005, pp. 1277–1282.

- “Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency.” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase-deficiency/.

- “Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency – Genetics Home Reference – NIH.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase-deficiency.

- Luzzatto, Lucio, and Elisa Seneca. “G6PD Deficiency: a Classic Example of Pharmacogenetics with on-Going Clinical Implications.” British Journal of Haematology, vol. 164, no. 4, 16 Apr. 2014, pp. 469–480., doi:10.1111/bjh.12665.

- Therrell, Bradford L., and Carmencita D. Padilla. “Newborn Screening in the Developing Countries.” Current Opinion in Pediatrics, vol. 30, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 734–739., doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000683.

Download the Nabta App

Related Articles

Why Does my Toddler Want to be Naked? (2024)

Find out why toddler want to be naked and get simple tips to manage it calmly, including sensory needs, new skills, and setting routines, The toddler years are marked by a variety of developmental milestones, one of which is the ability to dress and undress independently. While this new skill can be exciting for children, it can often [lead](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/lead/) to inconvenient or embarrassing situations for parents, such as toddlers wanting to be naked all the time. However, this behavior is quite common and typically not a cause for concern. Why Toddlers Want to Be Naked ----------------------------- * **Sensory Input:** The main possible reasons toddlers like to keep naked include sensory input. Clothing such as seams within socks or shirt tags may be uncomfortable for a child, and this sensation of discomfort may make them remove their clothes frequently. If you suspect the child is extremely sensitive to a trivial input, it may indicate a problem like sensory processing disorder, for which the pediatrician can be consulted. * **Undressing as an Achievable Developmental Milestone**: One needs to consider that this might be one of the primary ways a toddler achieves a milestone in their development. They may feel proud of their new skill and want to share it with others, no matter how frustrating this may be for the parent. * **Attention Seeking**: The toddler may sometimes undress for attention; this is particularly true if the parent responds strongly to the behavior. The reaction from a frustrated or embarrassed parent may elicit persistence in undressing with the child to get some form of response. This, therefore, means that how parents react significantly influences behavior. How to Handle Your Toddler’s Nakedness -------------------------------------- * **Stay calm**: Parents should not react humiliatingly to the child instead of getting angry but may respond calmly with no humiliating remarks. The parents may tell their children how good they are at undressing and ask them to wear their clothes. This should be responding neutrally to avoid further exaggeration of the behavior. You might try dialogue like, “Wow! Terrific. I can see you undress yourself like a big kid. Can you get dressed now and show me how you do that?” By acting like the undressing is no more of a big deal than dressing, this may stop the problem in its tracks. * **Allocate Times to be Undressed**: At times, parents will find it beneficial to establish times when the toddler can be undressed, such as in preparation for bath time or within the confines of the home. More often than not, these organized opportunities will enable toddlers to feel less anxious and content with the parameters that have been established. * **Remember, It’s Just a Phase**: Like most [phases of development](https://nabtahealth.com/article/qa-with-raquel-anderson-brain-development-in-a-12-month-old/), the compulsion to be naked shall pass. Children do appear to grow out of it eventually, and parents need a little patience and understanding. **References:** 1.A. R. Turner, P. S. Thompson, “Sensory Processing and the Toddler Years: A Study of Early Childhood Sensory Experiences,” Journal of Developmental Psychology, 2023. 2.M. E. Calloway, J. L. Roberts, “Undressing as a Developmental Milestone in Early Childhood,” Infant and Toddler Development Journal, 2024. 3.S. D. Harris, “Understanding Toddler Behavior: Reactions to Nakedness and Sensory Sensitivity,” Parenting Psychology Quarterly, 2024. 4.L. B. Wilkins, “How to Respond to Common Toddler Behaviors: Positive Guidance Techniques,” Journal of Child Development and Parenting, 2023. **Sources:** * What To Expect * Undressing (preferring to be naked). [American Academy of Pediatrics](https://www.aap.org/) * Emotional Development in Preschoolers. Powered by Bundoo®

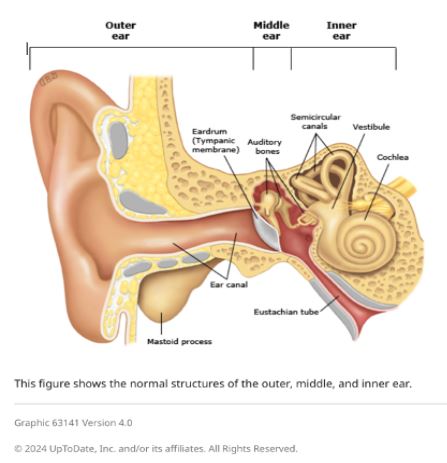

Fact or Fiction: Garlic Oil Helps Cure Ear Infections 2024

Garlic oil helps cure ear infections, natural [treatments](https://nabtahealth.com/) such as garlic oil are highly recommended as possessing antibacterial and antiviral properties. But does garlic oil live up to its reputation? The Science Behind Garlic and Ear Infections -------------------------------------------- Garlic has been used as a natural remedy for several centuries to cure various infections, among other ailments. The active ingredient, allicin, has been shown to exhibit antibacterial and antiviral properties that can help with the symptoms of an ear infection. A few studies confirm that allicin decreases the presence of certain bacteria and viruses, thus assisting in resolving the ear infection sooner. Yet anatomically, the ear makes this problematic as the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, acts to prevent direct delivery of oil or drops to the area of the middle ear where infections occur.  Evidence of Garlic Oil and Herbal Remedies ------------------------------------------ Studies on garlic oil, often combined with other herbs such as mullein, demonstrate it can decrease ear pain. A review published in 2023 reported that herbal ear drops, including those containing garlic, relieved pain in subjects with acute otitis media. However, researchers pointed out that while garlic oil may grant some advantages in the feeling of discomfort, its effect on the infection is limited by the eardrum barrier. Most infections will still self-resolve, but garlic oil can offer a natural alternative for pain management. Some studies in 2023 and 2024 also report that herbal extracts, including garlic, reduce dependence on heavy pain medications. Garlic is relatively cheaper and easier to access in herbal drops, particularly in many settings where prescription ear drops are not available. Safety and Proper Application of Garlic Oil ------------------------------------------- Being a potentially palliative resource, garlic needs to be used in the right manner. Experts advise against putting pure or undiluted garlic oil into the ear, as this can be too harsh and thus irritate or even injure sensitive ear tissue. Garlic extracts in commercially prepared herbal ear drops are recommended for use in the ear. In these products, garlic would have been diluted to safe levels while still being beneficial. Seeing a Health Professional ---------------------------- Consulting a health professional beforehand is very important when using garlic oil or any other herbal remedy against ear infections. Sometimes, ear infections result in complications, especially when not treated properly, and might cause recurrence. A healthcare provider will best help assess whether garlic oil or any other remedy may be indicated for each case and may recommend the safest treatment. Possible Benefits of Garlic Oil for Ear Health ---------------------------------------------- * Natural Pain Relief: Garlic oil’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory action soothes ear pain. * Cost-Effective: Garlic-based herbal remedies are generally cheaper than several prescription-based ear drops. * Readily Available Option: Garlic oil is readily available at health stores and can be ordered online. Current Research and Future Directions -------------------------------------- Herbal remedies, such as garlic oil, are still under research, especially for their role in pain relief and supporting natural recovery in light ear infections. Other studies investigate more advanced formulations that could let active compounds bypass the eardrum more effectively, thus giving a chance for enhanced effectiveness against middle-ear infections without the use of antibiotics. Key Takeaways ------------- * In effect, it has a minimal impact on the infection. It does not cure the disease but helps with earache because the membrane prevents the oil from reaching the middle ear. * Only use mild formulations. Commercially prepared herbal ear drops are very good compared to undiluted garlic oil. This is done to prevent irritation. * Consult a professional. Consult your health provider before this natural remedy, especially if you have recurring symptoms. References 1.Johnson, L., & Patel, R. (2023). [The Role of Herbal Remedies in Treating Ear Pain](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/): A Focus on Garlic Oil. Journal of Complementary Medicine, 61(2), 102-115. 2.Sharma, D., & Lee, H. (2024). Evaluating Garlic Extract for Natural Pain Relief in Ear Infections. Advances in Integrative Health, 42(1), 89-99. 3.Verhoeven, E., & Kim, S. (2023). Garlic and Herbal Extracts in Ear Infection Management. Health and Wellness Journal, 23(4), 167-178.

7 Healthy Eating Tips for Postpartum Weight Loss In 2024

Your new baby has arrived, and you are eager to get back into shape. However, [losing weight after pregnancy](https://nabtahealth.com/articles/7-healthy-eating-tips-for-postpartum-weight-loss/) takes time and patience, especially because your body is still undergoing many hormonal and metabolic changes. Most women will lose half their baby weight by 6-weeks postpartum and return to their pre-pregnancy weight by 6 months after delivery. For long-term results, keep the following tips in mind. Prior to beginning any diet or exercise, [please consult with your physician](https://nabtahealth.okadoc.com/). 1\. **Dieting too soon is unhealthy.** Dieting too soon can delay your recovery time and make you more tired. Your body needs time to heal from labor and delivery. Try not to be so hard on yourself during the first 6 weeks postpartum. 2\. **Be realistic**. Set realistic and attainable goals. It is healthy to lose 1-2 pounds per week. Don’t go on a strict, restrictive diet. Women need a minimum of 1,200 calories a day to remain healthy, and most women need more than that — between 1,500 and 2,200 calories a day — to keep up their energy and prevent mood swings. And if you’re nursing, you need a bare minimum of 1,800 calories a day to nourish both yourself and your baby. 3\. **Move it**. There are many benefits to exercise. Exercise can promote weight loss when combined with a reduced calorie diet. Physical activity can also restore your muscle strength and tone. Exercise can condition your abdominal muscles, improve your mood, and help prevent and promote recovery from postpartum depression. 4\. **Breastfeed**. In addition to the many benefits of breastfeeding for your baby, it will also help you lose weight faster. Women who gain a reasonable amount of weight and breastfeed exclusively are more likely to lose all weight six months after giving birth. Experts also estimate that women who breastfeed retain 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds) less than women who don’t breastfeed at six months after giving birth. 5\. **Hydrate**. Drink 8 or 9 cups of liquids a day. Drinking water helps your body flush out toxins as you are losing weight. Limit drinks like sodas, juices, and other fluids with sugar and calories. They can add up and keep you from losing weight. 6. **Don’t skip meals**. Don’t skip meals in an attempt to lose weight. It won’t help, because you’ll be more likely to binge at other meals. Skipping meals will also make you feel tired and grouchy. With a new baby, it can be difficult to find time to eat. Rather than fitting in three big meals, focus on eating five to six small meals a day with healthy snacks in between. 7\. **Eat the rainbow.** Stock up on your whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Consuming more fruits and vegetables along with whole grains and lean meats, nuts, and beans is a safe and healthy diet. ose weight after postpartum Is one of the biggest challenge women face worldwidely. Different Expertise and studies indicated that female might lose approximately 13 pounds’ weight which is around 6 KG in the first week after giving birth. The essential point here is that dieting not required for losing the weight, diet often reduce the amount of some important vitamins, minerals and nutrients. **Here are seven tips from the professional nutritionist perspective that can be considered for losing weight after postpartum these are;** 2\. Considered food like fish, chicken, nuts, and beans are excellent sources of protein and nutrients. 3\. A healthy serving of fat, such as avocado, chia seeds or olive oil 4\. With the balance diet please consider to drink plenty of water to stay hydrated. 5\. Regular exercise helps to shed extra pounds and improve overall health. 6\. Fiber-rich foods should be included to promote digestive health and support weight loss efforts. 7\. Don’t forget about self-care. By making these dietary changes and incorporating physical activity, you can achieve postpartum weight loss sustainably and healthily. **Sources:** * Center for Disease and Control and Prevention * Healthy Weight: it’s not dieting, it’s a lifestyle. Obstetrics and Gynecology * The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists * Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Powered by Bundoo®