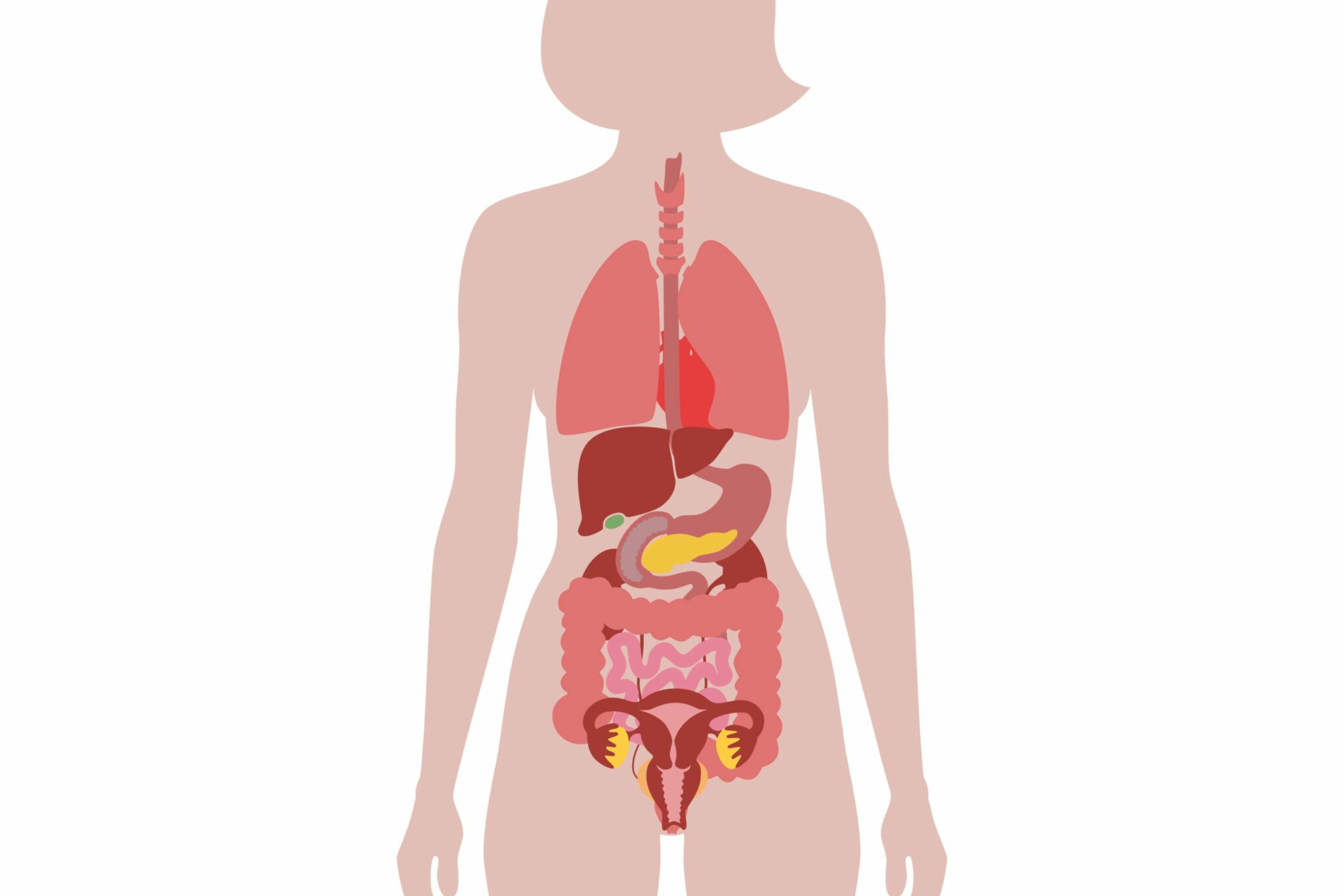

Areas of the Body Affected by Endometriosis

Endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue implants elsewhere in the body, often causing significant pain. The most frequent locations for this are the ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterosacral ligament. When the endometriosis affects these areas it is termed endopelvic. The most severe form of endopelvic endometriosis is rectovaginal. Fortunately not as common as other types, this deep, infiltrating endometriosis can encompass the vagina, rectum and rectovaginal septum, causing symptoms such as chronic pain, painful periods, dyspareunia and constipation.

The transplantation theory

The exact cause of endometriosis is unclear; however, one proposed mechanism is the transplantation theory. Cells of the endometrium are thought to migrate elsewhere in the body via the bloodstream and the lymphatic system. When the cells remain localised to the pelvic region it is known as retrograde menstruation. The ectopic implantation of endometrial tissue is the only known example of benign metastasis and, despite the proliferative abilities of the cells, it very rarely turns into cancer.

Extrapelvic endometriosis is more unusual. This is where the endometrial cells migrate further afield. Endometrial deposits have been identified in the abdominal wall, the thorax, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the urinary tract and very rarely in the large muscles surrounding the abdomen, buttocks and hips.

Endometriosis of the abdomen wall

The abdominal wall is the most common site for extrapelvic endometriosis. The deposits usually develop where there are surgical scars, for example, at the site of a previous Caesarean. At times it can be difficult to distinguish the pain caused by this condition from the pelvic pain characteristic of endopelvic endometriosis. However, the pain is often more focal and constant in nature, and not always associated with the menstrual cycle. Sometimes a palpable mass can be felt through the abdomen. This type of endometriosis is usually diagnosed using ultrasound and tissue biopsy. It is treated by excision of the deposits, although if not completely removed, symptoms can return over time.

Endometriosis of the thorax

The areas of the thorax most frequently affected by the endometriosis are the pleura, the pericardium and in rare cases the diaphragm. The method by which endometrial issue reaches the thorax is not well understood, although it is widely accepted to be via peritoneal fluid. If this is the case then lesions within the diaphragm must also be present to allow the passage of endometrial cells into the thoracic cavity. Thoracic endometriosis can also result in an embolism within the blood vessels of the lung, meaning less oxygen can be transported to the heart and around the body. Prompt surgical excision is essential.

Endometriosis of the GI tract

Endometriosis of the bowel is challenging to diagnose, with some patients waiting up to ten years for an accurate diagnosis. Symptoms include painful bowel movements, loss of appetite, cramping, nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation and bloating. Some patients will alternate between bouts of constipation and bouts of diarrhoea. Many of these symptoms are identical to those seen in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and thus the two conditions are frequently misdiagnosed. To add to the complexity of diagnosis, endometriosis and IBS often co-exist, with symptoms developing around the same time. Endometriosis symptoms will typically worsen during menstruation and there may be rectal bleeding .

Although up to 60% of all patients with endometriosis will experience some bowel-related issues, only 10-15% will actually have identifiable deposits on the bowel. Usually these are located superficially on the lower end of the small intestine (ileum), the first part of the large intestine (caecum) or the appendix, and thus, the standard treatment option is laparoscopic excision.

The reason so many patients experience bowel symptoms is thought to be due to the release of inflammatory factors, including prostaglandins. Excess prostaglandins stimulate the uterus to contract, causing the severe period pain some women with endometriosis suffer from; they can also cause the bowel to contract in a similar way. Endometrial deposits in adjacent areas can also aggravate the bowel, for example, when the uterosacral ligaments and/or rectovaginal septum are affected.

Surgery is usually the preferred treatment for bowel endometriosis. In the most severe cases, a section of the bowel may have to be cut out and the bowel rejoined. In less severe cases it may be sufficient to remove just the endometrial deposits. Bowel function may be permanently altered and certain foods might need to be avoided to prevent further aggravation after surgery.

Endometriosis of the liver and gallbladder is very rare.

Endometriosis of the urinary tract

Kidney endometriosis is rare and often asymptomatic. It will sometimes only be diagnosed when patients undergo investigative procedures for other renal conditions. Endometriosis can also form in the ureters, although usually only the left one is affected. This can cause obstruction of the urinary tract, necessitating surgery to remove the blockage.

Managing endometriosis

Treatment for any form of endometriosis will usually depend on the extent of the disease, as well as the patient’s wishes. It can be surgical, pharmaceutical, or a combination of the two. When symptoms are mild, simple monitoring and observation may be sufficient.

Pain is usually the predominant symptom of the condition; however, the ability of endometrial cells to migrate around the body certainly complicates the process of diagnosis.

Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and menopause.

Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you.

Sources:

- Machairiotis, N, et al. “Extrapelvic Endometriosis: a Rare Entity or an under Diagnosed Condition?” Diagnostic Pathology, vol. 8, 2 Dec. 2013, p. 194., doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194.

- Moawad, N S, and A Caplin. “Diagnosis, Management, and Long-Term Outcomes of Rectovaginal Endometriosis.” International Journal of Women’s Health, vol. 5, 8 Nov. 2013, pp. 753–763., doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S37846.

- Sinervo, K. Endometriosis and Bowel Symptoms. Center for Endometriosis Care, 2008, centerforendo.com/endometriosis-and-bowel-symptoms/. Last updated 2018.