Causes of Female Infertility – Environmental/Lifestyle Factors

There are a number of lifestyle and environmental factors that can influence infertility. Lifestyle factors are, by their nature, generally modifiable. This means that for women who are struggling to conceive, making simple lifestyle adjustments could improve their likelihood of falling pregnant. Some of the most well known lifestyle factors include:

Age

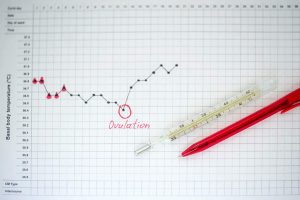

Many couples are choosing to delay having children, for personal, social or economic reasons. Fertility peaks and then declines over time, so a couple needs to carefully consider when the best time to start a family is. A woman is born with all the eggs she will ever have (over 1 million), but the number of viable eggs decreases during her lifespan, and only 400–500 are actually released from the ovaries during ovulation. With increasing age, there is a reduction in both the number and quality of eggs in the ovaries. The reduction in the number of eggs leads to changes in hormone levels, which further reduces a woman’s fertility. Increasing age also increases the time it takes for a woman to fall pregnant. In a European study with 782 couples, infertility was estimated at 8% for women aged 19-26 years, 13-14% for women aged 27-34 years and 18% for women aged 35-39 years. However, sometimes time and patience are key, and the authors concluded that many infertile couples would conceive if they tried for an additional year.

Nutrition

An improved diet can help improve fertility . Eating a folate-rich diet of dark, leafy greens, such as spinach is a good natural way to boost fertility. In fact, the NHS in the UK recommends that women who are trying to conceive take folic acid supplements (usually 0.4 mg daily) and continue with this throughout the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, as it can be difficult to get sufficient quantities from the diet alone. Avoiding too many trans fatty acids (TFA), will not only improve overall health and reduce the risk of heart disease; but also, improve the likelihood of falling pregnant. TFAs can adversely affect the shape and size of the sperm and the quality of the female oocyte.

Weight

Women who have a Body Mass Index (BMI) over 25 are classed as obese; obese women have a greater risk of experiencing recurrent early miscarriages. Women with a high BMI are also at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes and PCOS-like symptoms, which can also lead to infertility. Losing weight has been shown to improve fertility. On the other end of the spectrum, having a low BMI (<18.5) can also lead to problems conceiving. Low body fat increases the risk of ovarian dysfunction and women with a history of eating disorders are more likely to experience fertility issues.

Exercise

Moderate exercise is good for you and partaking in regular physical activity has been shown to improve fertility when coupled with weight loss in obese women. However, those who exercise excessively may be reducing their chances of conceiving. Specifically, when energy demand exceeds dietary energy intake, it can result in dysfunction of the hypothalamic axis and subsequent menstrual irregularities. Up to 56% of exercising women experience menstrual disturbances due to low energy availability. There is evidence that female athletes are more likely to suffer from iron-deficient anaemia, which can also affect menstruation and fertility. Iron is required for follicular development as well as endometrial thickening and a shortage can lead to difficulty in conceiving. Ensuring that, during training, the body has time to recover and the nutrients that are lost during strenuous exercise are replaced, will alleviate some of these risk factors.

Stress

Stress can be physical or psychological, and both types may negatively impact fertility. Unfortunately, up to 30% of women who visit a fertility clinic are likely to exhibit symptoms of psychological stress, such as depression or anxiety; for some women these manifestations are directly related to their struggles to conceive, for other women they occur as a result of underlying mental health issues. Regardless of the root cause, it is probable that their inability to conceive will exacerbate the situation further. A positive mood has been shown to correlate with increased live birth rates and, conversely, rates of oocyte fertilisation are reduced when stress levels are increased. The reasons why stress reduces fertility are not well understood, although the stress hormone alpha amylase has been implicated, possibly reducing blood flow to the Fallopian tube.

Smoking

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 250 million women smoke worldwide. Average rates are far higher in developed countries (22%) compared to developing countries (9%). Smoking is unhealthy on many levels, but in terms of fertility it disrupts ovarian function and reduces the ovarian reserve. Typically women that smoke go through the menopause between one and four years earlier than non-smokers. Women who smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day, have lower progesterone levels during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle, which can serve as a marker of anovulation. Without ovulation, fertilisation is not possible. Women who stop smoking double their chances of getting pregnant. The chemicals found in cigarette smoke can also compromise the uterine environment, making it inhospitable for embryo implantation and growth. Tobacco smoke also contains carcinogens, or cancer-causing substances. Carcinogens cause damage to DNA, which is the basic building material found in all cells of the human body, including the germ cells, which give rise to male sperm cells and female egg cells. Thus smoking can have a direct effect on the health of the reproductive sex cells. It is also important to consider the impact of passive smoking. In addition to contributing to male fertility issues, having a partner who smokes heavily can have reproductive consequences for the female who is regularly exposed to secondhand smoke, even if she does not smoke herself. Passive smoke exposure can be almost as detrimental as direct smoke inhalation and increases the risk of miscarriage, premature labour and birth defects.

Recreational and prescription drugs

Scientific studies are rare for ethical reasons and, certainly in the case of illicit drugs, under-reporting. However, the evidence does suggest that marijuana, for example, contains cannabinoids, which bind to reproductive structures and alter hormonal regulation. Prescription medications, such as those used to control autoimmune disease or those used in cancer therapy, may affect fertility. Consult your doctor if you are on any medication prior to starting a family. Your healthcare professional can ensure the drugs you are prescribed are safe for use during conception and pregnancy.

Alcohol and caffeine

Alcohol is one of the most widely used recreational substances worldwide and is associated with multiple reproductive risks. Perhaps the most well studied and widely understood of these risks are those related to foetal development. Alcohol readily crosses the placenta and therefore any alcohol consumed by the mother passes directly to her unborn child. High alcohol exposure can cause Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, which lead to behavioural and cognitive deficits and growth retardation. However, there are other issues that women who drink alcohol should consider if they are planning to start a family. Chronic, prolonged alcohol use can lead to menstrual cycle disturbances and a reduced ovarian reserve. There is a proven link between alcoholism and early menopause. Even moderate alcohol use reduces the success rates of infertility treatment, possibly due to an alteration in endogenous hormone levels and reduced endometrial receptivity. There is a suggested link between alcohol consumption and miscarriage, and, although studies performed to date have given conflicting results, the best advice is for pregnant women to completely abstain from alcohol and for all women to limit their intake whilst trying to conceive.

Caffeine is found in coffee, tea, carbonated drinks, energy drinks and chocolate. It is the most widely consumed psychostimulant worldwide; and drinking coffee is considered a cultural tradition in many countries of the Middle East. Pregnant women are advised to limit their caffeine consumption to between 200mg (European Food Safety Authority) and 300mg (WHO) a day, which equates to two to three cups of coffee. This is because of an increased risk of miscarriage in those who regularly consume high quantities of caffeine. It is not fully understood why caffeine increases the rate of miscarriage, but suggested mechanisms are altered levels of endogenous hormones and disrupted placental blood flow. Caffeine also crosses the placenta, so can have direct effects on the developing foetus. Women who regularly consume more than 300mg of caffeine a day might notice that they have shorter than average menstrual cycles, however, there is no clear data on the effect of high caffeine intake on other areas of reproductive capability. A final point to bear in mind is that caffeine is not the only bioactive substance in coffee. It is possible that the different ingredients may have a cocktail or synergistic effect, and more work is required to look at circulating caffeine levels as well as comparing the effects of decaffeinated drinks with their caffeine-filled equivalents.

Environmental exposures/toxins

These are amongst the most difficult factors to avoid, as they surround us in our day-to-day lives. Heavy metals, such as lead, mercury and boron can affect both male and female fertility. Lead is found in batteries, metal products, paints and pipes; it interrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and alters hormone levels. It also reduces sperm quality and can cause menstrual cycle irregularities in females. Boron, used to manufacture glass, ceramic and leather, has similar effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Mercury is found in thermometers, batteries and industrial emissions. It enters the food chain via tainted seafood and bioaccumulates in humans, negatively affecting fertility; disrupting spermatogenesis and potentially causing foetal abnormalities. Air pollution comes from particulate matter and ground-level ozone being released into the atmosphere. Gases such as carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide all contribute to the problem. These air pollutants come from, amongst other sources, vehicle emissions, the burning of fuels and industrial emissions. Air pollution has a significant impact on a number of physiological functions, including reproduction. It is very difficult to isolate specific pollutants, as usually people are simultaneously exposed to a number at the same time. It has also proved challenging to identify the specific mechanisms through which these particles impact fertility. They seem to interfere with the development of the male and female sex cells. Excessive exposure to air pollutants also has an association with increased miscarriage rates and foetal malformations, for reasons yet to be fully elucidated. Whilst absolute avoidance of air pollution is not possible, the message must be to raise awareness and, on a global scale, attempt to limit the release of harmful, ozone-damaging materials into the environment.

Endocrine disruptors

Endocrine disruptors affect male and female fertility. They mimic natural hormones, impeding normal hormone activity and altering the function of the endocrine system. They are widespread and found virtually everywhere, from manufacturing processes, to personal care products, medical applications, to cleaning products. Some of the most widely used, repeatedly shown to affect female fertility are:

- BPA (Bisphenol A). Used in the manufacture of plastics. Found in microwaveable containers and water bottles; as well as paints and adhesives. Associated with recurrent miscarriages and embryonic chromosomal abnormalities.

- Phthalates. Used to soften plastics. Found in cosmetics, perfumes, toys, pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Cause ovulatory irregularities, reduced fertility and a longer time to pregnancy. Also linked to early puberty.

- Solvents. Found in plastics, resins, glues, paints, dyes, detergents, pesticides, nail varnish, insulation, food containers, cleaning products, amongst other things. Lead to hormonal changes and reduced fertility.

It is quite obvious from the list above that endocrine disruptors are prolific, and have unfortunately become a central part of modern life. Therefore,avoiding all exposure to potential endocrine disrupting chemicals is not feasible. However, minimising exposure to some known toxins, may help couples who are struggling to conceive.

Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and menopause.

Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you.

Sources:

- Carré, J, et al. “Does Air Pollution Play a Role in Infertility?: a Systematic Review.” Environmental Health, vol. 16, no. 1, 28 July 2017, p. 82., doi:10.1186/s12940-017-0291-8.

- Chalupka, S, and A N Chalupka. “The Impact of Environmental and Occupational Exposures on Reproductive Health.” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, vol. 39, no. 1, 2010, pp. 84–102., doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01091.x.

- “Female Smoking.” World Health Organisation, www.who.int/tobacco/en/atlas6.pdf

- “How Stopping Smoking Boosts Your Fertility Naturally.” Cleveland Clinic, 16 Apr. 2019, health.clevelandclinic.org/how-stopping-smoking-boosts-your-fertility-naturally/.

- Lyngsø, J, et al. “Association between Coffee or Caffeine Consumption and Fecundity and Fertility: a Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Epidemiology, vol. 9, 15 Dec. 2017, pp. 699–719., doi:10.2147/CLEP.S146496.

- Palomba, S, et al. “Lifestyle and Fertility: the Influence of Stress and Quality of Life on Female Fertility.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, vol. 16, no. 1, 2 Dec. 2018, p. 113., doi:10.1186/s12958-018-0434-y.

- Petkus, D L, et al. “The Unexplored Crossroads of the Female Athlete Triad and Iron Deficiency: A Narrative Review.” Sports Medicine, vol. 47, no. 9, Sept. 2017, pp. 1721–1737., doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0706-2.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. “Smoking and Infertility.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 90, no. 5 (Suppl), Nov. 2008, pp. S254–S259., doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.035.

- Sharma, R, et al. “Lifestyle Factors and Reproductive Health: Taking Control of Your Fertility.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, vol. 11, no. 66, 16 July 2013, doi:10.1186/1477-7827-11-66.

- Van Heertum, K, and B Rossi. “Alcohol and Fertility: How Much Is Too Much?” Fertility Research and Practice, vol. 3, 10 July 2017, p. 10., doi:10.1186/s40738-017-0037-x.

- “What Are Some Possible Causes of Female Infertility? .” National Institutes of Health, www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/infertility/conditioninfo/causes/causes-female.

- “What Lifestyle and Environmental Factors May Be Involved with Infertility in Females and Males? .” National Institutes of Health, www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/infertility/conditioninfo/causes/lifestyle.