What is Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia?

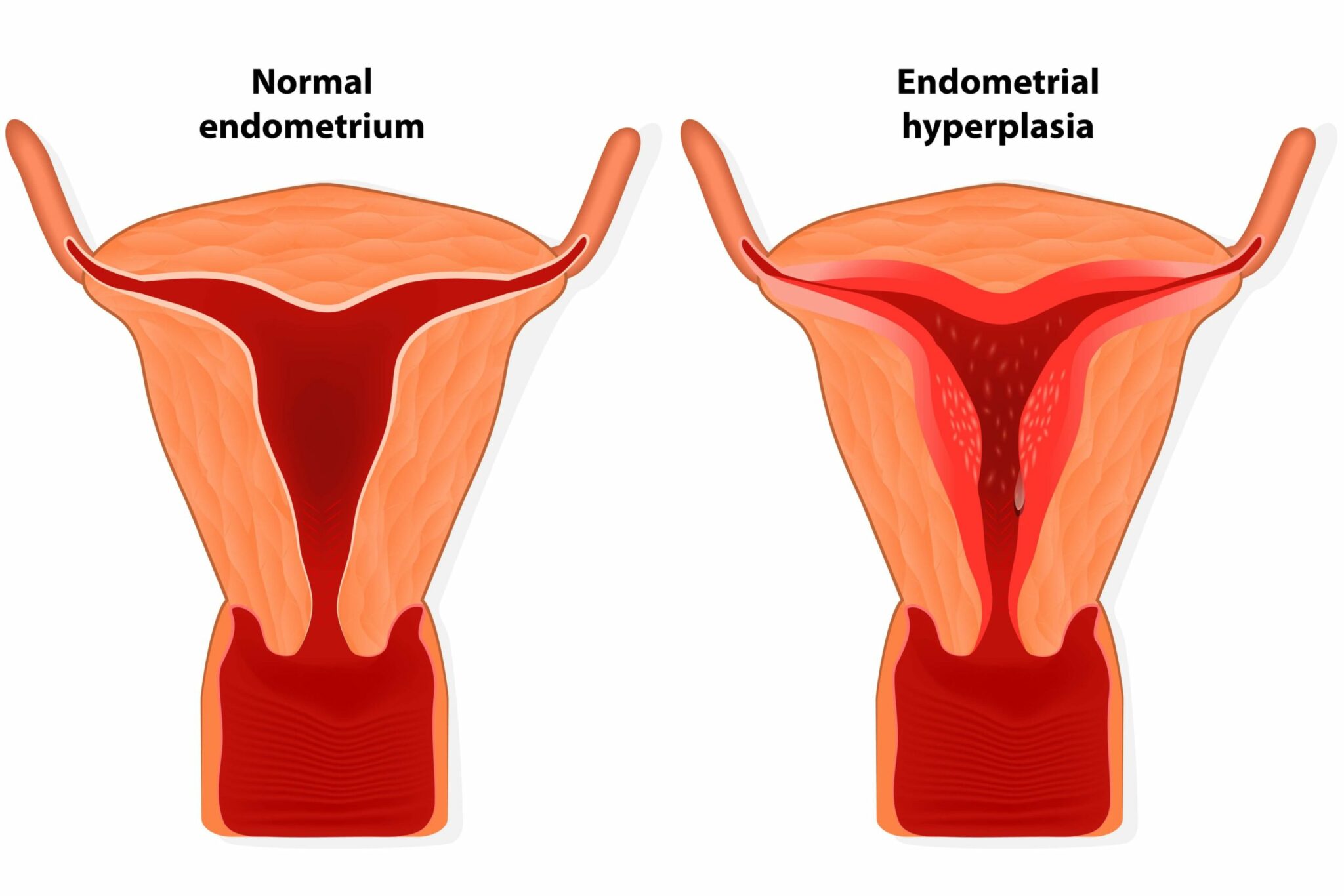

Endometrial hyperplasia occurs when the lining of the uterus becomes abnormally thick. Usually it happens when the endometrial glands undergo abnormal (hyperplastic) proliferation. There are two types: atypical and non-atypical hyperplasia. Of particular concern is atypical endometrial hyperplasia (AEH), which is very often seen as a precursor of endometrial cancer (also called womb or uterine cancer). In fact, another name for the condition is ‘carcinoma in-situ’.

Not all atypical lesions develop into cancer; some regress without the need for treatment, however, it is estimated that up to 40% of women who are diagnosed with AEH will go on to develop endometrial carcinoma. Women with non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia may also develop cancer, but their chances are much lower (≤ 5%).

Risk Factors for atypical endometrial hyperplasia

The predominant cause of AEH is chronic exposure of the endometrium to unopposed oestrogens. Obesity is a risk factor for AEH (and endometrial cancer) in postmenopausal women because adipose tissue becomes a major source of oestrogens once the ovaries stop functioning. Adipose tissue contains high levels of an enzyme called aromatase, which converts circulating androgens into oestrogens.

One of the reasons why the incidence of AEH is increasing in younger women is because of the rising rates of PCOS. PCOS is a hormonal condition, affecting up to 10% of females of reproductive age. It is confusingly named, as not all women with PCOS will have polycystic ovaries; a physiologically more accurate (if less user-friendly) name would be hyperandrogenic anovulation, as many women experience anovulatory menstrual cycles, with an excess of androgens. Without ovulation, the lining of the uterus will not be shed and the endometrial cells will continue to proliferate.

Other risk factors include hormone therapy, for example long-term Tamoxifen treatment, or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Medications such as these, result in exposure of the endometrium to exogenous oestrogen. There are also various genetic mutations known to increase a woman’s susceptibility to developing AEH. Smoking may also be a risk factor.

An alternative cause of AEH is immunosuppression, with one study showing that women who had undergone a kidney transplant were significantly more likely to develop AEH.

Some women with endometrial polyps find that they have AEH, although the likelihood of one causing the other is slim. It is more likely that the two coexist as they are both driven by an excess of oestrogen.

Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment

The main symptom of AEH is abnormal uterine bleeding. Approximately 15% of women who experience postmenopausal bleeding are found to have AEH. Abnormal bleeding can be due to other factors, including polyps, but should always be investigated by your doctor.

Most cases of AEH will be diagnosed by endometrial sampling with a biopsy or dilation & curettage. Treatment typically depends on the age of the woman, as well as her reproductive status. Postmenopausal females will usually undergo a hysterectomy; however, those that are hoping to preserve their fertility may attempt progesterone therapy first. For those women who opt against surgery, regular monitoring is essential due to the high association between AEH and cancer.

The challenges of AEH

Diagnosing and classifying AEH is not without its difficulties. For a start, the ‘normal’ endometrium is a dynamic structure that is constantly undergoing phases of proliferation, shedding and regrowth. Determining when this cellular growth is abnormal is not easy.

Furthermore, as yet, there is no way of definitively establishing which instances of AEH will progress to endometrial cancer. The current treatment of choice is preventative in nature, involving removal of the entire uterus via hysterectomy. Whilst, this irrefutably eliminates the risk of endometrial cancer, it is a drastic approach, particularly considering a significant proportion of women who have AEH will not go on to develop cancer. There is an urgent need to identify a biomarker capable of predicting, with a high degree of certainty, which lesions will become cancerous and which lesions are likely to spontaneously regress with time.

Nabta is reshaping women’s healthcare. We support women with their personal health journeys, from everyday wellbeing to the uniquely female experiences of fertility, pregnancy, and menopause.

Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you.

Sources:

- Bobrowska, K., et al. “High Rate of Endometrial Hyperplasia in Renal Transplanted Women.” Transplantation Proceedings, vol. 38, no. 1, 2006, pp. 177–179., doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.12.007.

- Ginsburg, Ophira, et al. “The Global Burden of Women’s Cancers: a Grand Challenge in Global Health.” The Lancet, vol. 389, no. 10071, 25 Feb. 2017, pp. 847–860., doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31392-7.

- Kelly, P, et al. “Endometrial Hyperplasia Involving Endometrial Polyps: Report of a Series and Discussion of the Significance in an Endometrial Biopsy Specimen.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 114, no. 8, 12 June 2007, pp. 944–950., doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01391.x.

- Lacey, J V, et al. “Endometrial Carcinoma Risk among Women Diagnosed with Endometrial Hyperplasia: the 34-Year Experience in a Large Health Plan.” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 98, no. 1, 15 Jan. 2008, pp. 45–53., doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604102.

- Manna, P.r., et al. “Dysregulation of Aromatase in Breast, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancers.” Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science Molecular and Cellular Changes in the Cancer Cell, vol. 144, 2016, pp. 487–537., doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.10.002.

- Murali, Rajmohan, et al. “Classification of Endometrial Carcinoma: More than Two Types.” The Lancet Oncology, vol. 15, no. 7, June 2014, pp. e268–e278., doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70591-6.

- Sanderson, Peter A., et al. “New Concepts for an Old Problem: the Diagnosis of Endometrial Hyperplasia.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 23, no. 2, 1 Mar. 2017, pp. 232–254., doi:10.1093/humupd/dmw042.