Gynoid Fat (Hip Fat and Thigh Fat): Possible Role in Fertility

Dr. Kate Dudek • November 10, 2024 • 5 min read

Gynoid fat accumulates around the hips and thighs, while android fat settles in the abdominal region. The sex hormones drive the distribution of fat: Estrogen keeps fat in the gluteofemoral areas (hips and thighs), whereas testosterone causes fat deposition in the abdominal area.

Hormonal Influence on Fat Distribution

The female sex hormone estrogen stimulates the accumulation of gynoid fat, resulting in a pear-shaped figure, but the male hormone testosterone induces android fat, yielding an apple-shaped body. Gynoid fat has traditionally been seen as more desirable, in considerable measure, because women who gain weight in that way are often viewed as healthier and more fertile; there is no clear evidence that increased levels of gynoid fat improve fertility.

Changing Shapes of the Body across Time

Body fat distribution varies with age, gender, and genetics. In childhood, the general pattern of body shape is similar between boys and girls; at puberty, however, sex hormones come into play and influence body fat distribution for the rest of the reproductive years. Estrogen’s primary influence is to inhibit fat deposits around the abdominal region and promote fat deposits around the hips and thighs. On the other hand, testosterone promotes abdominal fat storage and blocks fat from forming in the gluteofemoral region.

In women, disorders like PCOS may be associated with higher levels of androgens including testosterone and lower estrogen, leading to a more male pattern of fat distribution.

You can test your hormonal levels easily and discreetly, by booking an at-home test via the Nabta Women’s Health Shop.

Waist Circumference (WC)

It is helpful in the evaluation and monitoring of the treatment of obesity using waist circumference. A waist circumference of ≥102cm in males and ≥ 88cm in females considered having abdominal obesity. Note that waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) doesn’t have an advantage over waist circumference.

After menopause, a woman’s WC will often increase, and her body fat distribution will more closely resemble that of a normal male. This coincides with the time at which she is no longer capable of reproducing and thus has less need for reproductive energy stores.

Health Consequences of Low WHR

Research has demonstrated that low WC women are at a health advantage in several ways, as they tend to have:

- Lower incidence of mental illnesses such as depression.

- Slowed cognitive decline, mainly if some gynoid fat is retained postmenopause

- A lower risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers.

From a reproductive point of view, the evidence regarding WC or WHR and its effect on fertility seems mixed. Some studies suggest that low WC or WHR is indeed associated with a regular menstrual cycle and appropriate amounts of estrogen and progesterone during ovulation, which may suggest better fecundity. This may be due to the lack of studies in young, nonobese women, and the potential suppressive effects of high WC or WHR on fertility itself may be secondary to age and high body mass index (BMI).

One small-scale study did suggest that low WHR was associated with a cervical ecology that allowed easy sperm penetration, but that would be very hard to verify. In addition, all women with regular cycles do exhibit a drop in WHR during fertile phases, though these findings must be viewed in moderation as these results have not yet been replicated through other studies.

Evolutionary Advantages of Gynoid Fat

Women with higher levels of gynoid fat and a lower WHR are often perceived as more desirable. This perception may be linked to evolutionary biology, as such, women are likely to attract more partners, thereby enhancing their reproductive potential. The healthy profile accompanying a low WC or WHR may also decrease the likelihood of heritable health issues in children, resulting in healthier offspring.

Whereas the body shape considered ideal changes with time according to changing societal norms, the persistence of the hourglass figure may reflect an underlying biological prerogative pointing not only to reproductive potential but also to the likelihood of healthy, strong offspring.

New Appreciations and Questions

-

**Are there certain dietary or lifestyle changes that beneficially influence the deposition of gynoid fat?

**

Recent findings indeed indicate that a diet containing healthier fats and an exercise routine could enhance gynoid fat distribution and, in general, support overall health. -

**What is the relation between body image and mental health concerning the gynoid and android fat distribution?

**

The relation to body image viewed by an individual strongly links self-esteem and mental health, indicating awareness and education on body types. -

**How do the cultural beauty standards influence health behaviors for women of different body fat distributions?

**

Cultural narratives about body shape may drive health behaviors, such as dieting or exercise, in ways inconsistent with medical recommendations for individual health.

References

1.Shin, H., & Park, J. (2024). Hormonal Influences on Body Fat Distribution: A Review. Endocrine Reviews, 45(2), 123-135.

2.Roberts, J. S., & Meade, C. (2023). The Effects of WHR on Health Outcomes in Women: A Systematic Review. Obesity Reviews, 24(4), e13456.

3.Chen, M. J., & Li, Y. (2023). Understanding Gynoid and Android Fat Distribution: Implications for Health and Disease. Journal of Women’s Health, 32(3), 456-467.

4.Hayashi, T., et al. (2023). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Its Impact on Body Fat Distribution: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 234-241.

5.O’Connor, R., & Murphy, E. (2023). Sex Hormones and Fat Distribution in Women: An Updated Review. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental, 143, 155-162.

6.Thomson, R., & Baker, M. (2024). Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health: The Role of Fat Distribution. Health Psychology Review, 18(1), 45-60.

7.Verma, P., & Gupta, A. (2023). Cultural Influences on Body Image and Health Behaviors: A Global Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (MDPI), 20(5), 3021.

Download the Nabta App

Related Articles

9 Natural Induction Methods Examined: What Does the Evidence Say?

Towards the end of [pregnancies](https://nabtahealth.com/article/ectopic-pregnancies-why-do-they-happen/), many women try methods of natural induction. The evidence supporting various traditional methods is variable, and benefits, side effects, and notable potential health risks are present. Understanding what science says can help individuals make informed choices in consultation with a provider. Induction of Natural Labour induction Myths, Realities and Precautions ---------------------------------------------------------------------- The following section will review nine standard natural induction methods, discussing the proposed mechanism, evidence, and safety considerations. Avoid potential hazards by avoiding risky labor triggers and get advice from your [obstetrician](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/obstetrician/) before choosing any method mentioned below. Castor Oil ---------- Castor oil has been used throughout the centuries to induce labor, and studies suggest that it does so on some 58% of occasions. This oil stimulates prostaglandin release, which in turn may have the result of inducing cervical changes. Adverse effects, such as nausea and [diarrhea](https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diarrhea/symptoms-causes/syc-20352241), are common, however. Castor oil should be used near the [due date](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/due-date/) and with extreme caution, given its contraindication earlier in pregnancy. Breast Stimulation ------------------ The historical and scientific backing of breast stimulation is based on the release of oxytocin to soften the [cervix](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cervix/). A study has shown that, with this method, cervical ripening may be achieved in about 37% of cases. However, excessive stimulation may cause uterine hyperstimulation, and guidance from professionals may be essential. Red Raspberry Leaf ------------------ Red raspberry leaf is generally taken as a tea and is thought to enhance blood flow to the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/) and stimulate [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/). Traditional use, however, is tempered by a relative lack of scientific research regarding its effectiveness. Animal studies have suggested possible adverse side effects, and no human data are available that supports a correlation with successful induction of labor. Sex --- Sex is most commonly advised as a natural induction method based on the principle that sex introduces [prostaglandins](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/prostaglandins/) and oxytocin, and orgasm induces uterine [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/). The few studies in the literature report no significant effect on labor timing. Generally safe for women when pregnancy is otherwise low-risk but may not speed labor. Acupuncture ----------- Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese practice that has been done to stimulate labor through the induction of hormonal responses. However, some studies show its effectiveness in improving cervical ripening but not necessarily inducing active labor. An experienced practitioner would appropriately consult its safe application during pregnancy. Blue and Black Cohosh --------------------- Native American groups traditionally utilize blue and black cohosh plants for gynecological use. These plants are highly discouraged nowadays from inducing labor because of the risk of toxicity they may bring. Although they establish substantial [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/), they have been observed to sometimes cause extreme complications-possibly congenital disabilities and heart problems in newborns Dates ----- Some cultural beliefs view dates as helping induce labor by stimulating the release of oxytocin. They do not help stimulate uterine [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/) to start labor, but clinical research does support that dates support cervical [dilation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/dilation/) and reduce the need for medical inductions during labor. They also support less hemorrhaging post-delivery when consumed later in pregnancy. Pineapple --------- Something in pineapple called bromelain is an [enzyme](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/enzyme/) that is supposed to stimulate [contractions](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/contraction/) of the [uterus](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/uterus/). Animal tissue studies have determined it would only work if applied directly to the tissue, so it’s doubtful this is a natural method for inducing labor. Evening Primrose Oil -------------------- Evening Primrose Oil, taken almost exclusively in capsule form, is another common naturopathic remedy to ripen the [cervix](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cervix/). Still, studies are very few and indicate a greater risk of labor complications, such as intervention during delivery, and it is not recommended very often. Safety and Consultation ----------------------- Many of these methods are extremely popular; however, most are unsupported by scientific data. Any method should be discussed with a healthcare provider because all may be contraindicated depending on gestational age, maternal health, and pregnancy risk levels. Try going for a walk, have a warm bath and relax while you’re waiting for your baby. “Optimal fetal positioning,” can help baby to come into a better position to support labor. You can try sitting upright and leaning forward by sitting on a chair backward. Conclusion ---------- Natural methods of inducing labor vary widely in efficacy and safety. Practices like breast stimulation and dates confer some benefits, while others, such as those involving castor oil and blue cohosh, carry risks. Based on the available evidence, decisions about labor induction through healthcare providers are usually the safest. You can track your menstrual cycle and get [personalised support by using the Nabta app](https://nabtahealth.com/nabta-app/). Get in touch if you have any questions about this article or any aspect of women’s health. We’re here for you. Sources : 1.S. M. Okun, R. A. Lydon-Rochelle, and L. L. Sampson, “Effect of Castor Oil on Induction of Labor: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 2023. 2.T. K. Ford, H. H. Snell, “Effectiveness of Breast Stimulation for Cervical Ripening and Labor Induction: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2023. 3.R. E. Smith, D. M. Wilson, “Red Raspberry Leaf and Its Role in Pregnancy and Labor: A Critical Review,” Alternative Medicine Journal, 2024. 4.A. L. Jameson, “Sexual Activity and Its Effect on Labor Induction: A Review,” International Journal of Obstetrics, 2023. 5.B. C. Zhang, Z. W. Lin, “Acupuncture as a Method for Labor Induction: Evidence from Recent Clinical Trials,” Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2023. 6.D. K. Patel, J. M. Williams, “Toxicity of Blue and Black Cohosh in Pregnancy: Case Studies and Clinical Guidelines,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2024. 7.M. J. Abdullah, F. E. Azzam, “The Role of Dates in Pregnancy: A Review of Effects on Labor and Birth Outcomes,” Nutrition in Pregnancy, 2024. 8.S. L. Chung, L. M. Harrison, “Pineapple and Its Potential Role in Labor Induction: A Review,” Journal of Obstetric and [Perinatal](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/perinatal/) Research, 2023. 9.L. M. Weston, A. R. Franklin, “Evening Primrose Oil for Labor Induction: A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Alternative Therapies in Pregnancy, 2024. Patient Information Induction of labour Women’s Services. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2024, from https://www.enherts-tr.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Induction-of-Labour-v5-09.2020-web.pdf

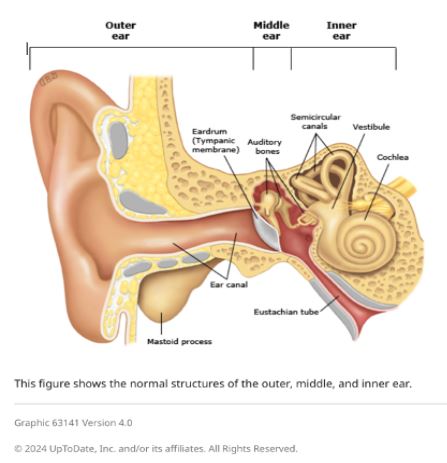

Fact or Fiction: Garlic Oil Helps Cure Ear Infections 2024

Garlic oil helps cure ear infections, natural [treatments](https://nabtahealth.com/) such as garlic oil are highly recommended as possessing antibacterial and antiviral properties. But does garlic oil live up to its reputation? The Science Behind Garlic and Ear Infections -------------------------------------------- Garlic has been used as a natural remedy for several centuries to cure various infections, among other ailments. The active ingredient, allicin, has been shown to exhibit antibacterial and antiviral properties that can help with the symptoms of an ear infection. A few studies confirm that allicin decreases the presence of certain bacteria and viruses, thus assisting in resolving the ear infection sooner. Yet anatomically, the ear makes this problematic as the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, acts to prevent direct delivery of oil or drops to the area of the middle ear where infections occur.  Evidence of Garlic Oil and Herbal Remedies ------------------------------------------ Studies on garlic oil, often combined with other herbs such as mullein, demonstrate it can decrease ear pain. A review published in 2023 reported that herbal ear drops, including those containing garlic, relieved pain in subjects with acute otitis media. However, researchers pointed out that while garlic oil may grant some advantages in the feeling of discomfort, its effect on the infection is limited by the eardrum barrier. Most infections will still self-resolve, but garlic oil can offer a natural alternative for pain management. Some studies in 2023 and 2024 also report that herbal extracts, including garlic, reduce dependence on heavy pain medications. Garlic is relatively cheaper and easier to access in herbal drops, particularly in many settings where prescription ear drops are not available. Safety and Proper Application of Garlic Oil ------------------------------------------- Being a potentially palliative resource, garlic needs to be used in the right manner. Experts advise against putting pure or undiluted garlic oil into the ear, as this can be too harsh and thus irritate or even injure sensitive ear tissue. Garlic extracts in commercially prepared herbal ear drops are recommended for use in the ear. In these products, garlic would have been diluted to safe levels while still being beneficial. Seeing a Health Professional ---------------------------- Consulting a health professional beforehand is very important when using garlic oil or any other herbal remedy against ear infections. Sometimes, ear infections result in complications, especially when not treated properly, and might cause recurrence. A healthcare provider will best help assess whether garlic oil or any other remedy may be indicated for each case and may recommend the safest treatment. Possible Benefits of Garlic Oil for Ear Health ---------------------------------------------- * Natural Pain Relief: Garlic oil’s antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory action soothes ear pain. * Cost-Effective: Garlic-based herbal remedies are generally cheaper than several prescription-based ear drops. * Readily Available Option: Garlic oil is readily available at health stores and can be ordered online. Current Research and Future Directions -------------------------------------- Herbal remedies, such as garlic oil, are still under research, especially for their role in pain relief and supporting natural recovery in light ear infections. Other studies investigate more advanced formulations that could let active compounds bypass the eardrum more effectively, thus giving a chance for enhanced effectiveness against middle-ear infections without the use of antibiotics. Key Takeaways ------------- * In effect, it has a minimal impact on the infection. It does not cure the disease but helps with earache because the membrane prevents the oil from reaching the middle ear. * Only use mild formulations. Commercially prepared herbal ear drops are very good compared to undiluted garlic oil. This is done to prevent irritation. * Consult a professional. Consult your health provider before this natural remedy, especially if you have recurring symptoms. References 1.Johnson, L., & Patel, R. (2023). [The Role of Herbal Remedies in Treating Ear Pain](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/): A Focus on Garlic Oil. Journal of Complementary Medicine, 61(2), 102-115. 2.Sharma, D., & Lee, H. (2024). Evaluating Garlic Extract for Natural Pain Relief in Ear Infections. Advances in Integrative Health, 42(1), 89-99. 3.Verhoeven, E., & Kim, S. (2023). Garlic and Herbal Extracts in Ear Infection Management. Health and Wellness Journal, 23(4), 167-178.

Why are Certain Individuals at a Higher Risk of Being Affected by a SARS CoV-2 Infection?

Coronavirus disease 2019 ([COVID-19](https://nabtahealth.com/covid-19/)) has affected large parts of the world and has now reached pandemic status. As of the 22nd of May, the SARS-CoV-2 virus had spread to 188 countries with over 5 million cases and more than 300,000 deaths worldwide. This disease is caused by a respiratory virus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV-2). More data is emerging on the variability of outcomes caused by COVID-19. The infection affects populations and individuals in different ways, and this seems to be dependent on a combination of biological, [socioeconomic](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/socioeconomic/) or [sociodemographic](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/sociodemographic/) factors, which may or may not be linked to underlying health conditions. Some individuals may be infected with the virus and not experience any symptoms, whilst the same infection in others may cause severe respiratory disease, multi-organ failure and death. The available data surrounding the signs and risks of infection by SARS CoV-2, as well as the outcomes and treatments of COVID-19, is continuously evolving. Provision of updated, evidence-based, information using the most recent clinical research and data will help mitigate the spread of the infection, and protect those who are more vulnerable around us. Watching out for the most common signs of the infection such as a fever, cough and shortness of breath, even if the symptoms are mild, is paramount to protecting yourself and others. Staying at home, and maintaining self-isolation and distancing measures if you have any symptoms of COVID-19 reduces the risk of infecting others . If you are living with others and know that you have been infected, wear a mask in their presence to limit their exposure and ask them to do the same. If possible, stay at least 2 metres away from others at home, limit contamination of surfaces and other communal facilities, and avoid sharing household items. These measures are particularly important for those who are at increased risk of severe disease once infected with the virus. This article provides an outline of the different risk factors that make individuals more vulnerable to the acquisition of severe or critical symptoms following infection with SARS CoV-2, based on the most current reports and research. #### **Demographics** Characteristics such as gender, age, and weight have been shown to contribute to the way that a person responds once exposed to, or infected with, SARS CoV-2. Case-fatality rates, defined as the rate of death from COVID-19 from the total number of diagnosed cases, vary worldwide. Data gathered to date by Johns Hopkins University show that case-fatality rates range from 0-16% by country, suggesting that there are ethnic and [socioeconomic](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/socioeconomic/) factors that contribute to the risk of dying from COVID-19. As more data emerges, and with further research, the clinical and scientific community will begin to understand the role that genetic, social, and cultural factors play in controlling the rates and outcomes of infection. To date, three main demographic factors present disproportionate risks as summarised below. #### **Gender** COVID-19 appears to adversely affect the male population more than the female. Men are at increased risk of developing moderate to severe symptoms once infected with the SARS CoV-2 virus. As a result, data published to date is showing that men are, on average, twice as likely to be critically hospitalised or die once infected by the virus. More research is required to understand how females are more protected from SARS CoV-2 than men, but it is possible to extrapolate this based on the fact that the X chromosome carries a number of important genes that have an important role in the regulation of the immune system. Therefore, the reduced susceptibility of females to the acquisition of symptoms associated with viral infection can be attributed to the X chromosome. In males, the presence of a single X chromosome, compared to the two copies that females carry, means that they can be more immuno-compromised under certain conditions. There are also lifestyle and cultural aspects which can put men in a higher risk category than women such as [smoking](#smoking) and alcohol. #### **Age** Individuals of any age can contract SARS CoV-2, with or without becoming symptomatic. To date, COVID-19 has affected significantly more individuals in the 65 and over age bracket, and less of the younger population. Studies have shown that advanced age puts individuals at a higher risk of experiencing severe symptoms once infected with SARS CoV-2; meaning that this age group is more likely to require hospitalisation. Age also correlates with the acquisition of non-communicable disorders such as [hypertension](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hypertension/), chronic renal disease and diabetes. In the context of COVID-19, over 70% of those who have been hospitalised with the infection over the age of 65 have at least one underlying health condition. In general, the ability of our bodies to regenerate slows down with age, and this applies to all organs, including the skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver and immune system. As a result, the older you are, the less likely your body is able to effectively or rapidly clear infections. Maintaining a balanced diet and partaking in regular exercise gives you a better chance of maintaining a healthy body to fight infections. This is particularly important if you are in the older population group. However, despite the clear correlation between age and disease severity, certain young adults and children can also experience critical symptoms following infection with SARS CoV-2 for reasons that are not yet well understood. Caution, protection and healthy lifestyle choices must be adopted by all. #### **Body Mass Index** Your body weight can be used as an indicator to determine how at risk you are of developing severe or critical COVID-19 symptoms. An optimal [Body Mass Index](https://nabtahealth.com/what-is-body-mass-index-bmi/) ([BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/)) is 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 and if you lie within this range, you are considered to have a healthy weight. People in this category have enough body fat to function effectively. Body fat, or adipose tissue, is an essential component of every organ and cell in our body; it has multiple roles, including insulation, energy storage, and the maintenance of hormones. Fat cells are also a source of [stem cells](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/stem-cells/) which can differentiate into other cell types, such as bone and nerve cells, as required. These [stem cells](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/stem-cells/) therefore, have regenerative capabilities which are able to replace damaged or otherwise compromised tissues in our body as needed. Overweight individuals with a [BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/) above 25 kg/m2 and obese individuals with a [BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/) above 30 kg/m2 are at higher risk of developing multiple health disorders, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer. They are also more likely to be severely or chronically symptomatic if infected by SARS CoV-2. Having an excess of body fat means you are likely to be in a chronic state of low-grade [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/), which can impair your immune system’s response to infection. If infected, the obese are more likely to be hospitalised because their bodies are unable to fight the infection effectively, either as a direct correlation of excess body fat, or as an indirect correlation with the other health disorders that accompany obesity and which put individuals at a higher risk. If you have a [BMI](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/bmi/) below 18.5 kg/m2 you are classed as being underweight, meaning that your body is not storing enough body fat, giving you less overall protection. Being underweight weakens your immune system and puts you at increased risk of developing severe COVID-19 symptoms. Individuals who are underweight may be malnourished, and as a result may lack some of the essential nutrients, vitamins and minerals necessary for their cells and organs to function properly. This makes them more vulnerable to any external challenges or insults, such as complications arising from infection with a virus. Obese, overweight and underweight individuals should consider contacting a local healthcare provider and a nutritionist who can help them make a healthy and monitored weight loss or gain plan. #### **Underlying health conditions** COVID-19 has shown selectivity towards vulnerable individuals with underlying non-communicable disorders (NCDs). Some of the most prevalent NCDs include type 2 diabetes, [hypertension](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hypertension/), cardiovascular disease, chronic lung conditions, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease and cancer. This trend is consistent world-wide, as more statistics on patients emerge from the clinical and scientific community at large. Here, we outline a number of NCDs which have been shown to impact responses to the infection, and explore why individuals with these conditions are at risk of more severe COVID-19 symptoms. #### **Diabetes mellitus** If you have diabetes, you are unable to properly regulate blood glucose levels due to insufficient insulin production or reduced insulin sensitivity. Lack of insulin, or the inability of cells to respond to insulin, results in high blood glucose levels which puts you in a hyperglycaemic state. Under normal conditions, one of insulin’s functions (it has many others) is to signal your body to activate white blood cells, which are the main cells in our blood and lymph nodes that fight infections. Therefore, when the body is unable to produce sufficient amounts of insulin, a dysfunction of the immune system may occur, putting the individual at risk. A compromised immune system will be less able to control the spread of, and manage the symptoms associated with, invading pathogens such as SARS CoV-2. Being in a hyperglycemic state puts pressure on one’s body, which can result in damage to multiple organs such as the heart, kidney and nervous system . Individuals with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes are, therefore, at higher risks of developing health complications such as the acquisition of [cardiovascular disease](#CVdisease), [renal disease](#kidney) and peripheral nerve damage which also in turn put them at a higher risk of being negatively affected by infections and other external pressures. If you are diabetic, it is important to keep taking your medications as required. Those who are on insulin replacement therapy should monitor their body’s sensitivity to insulin which may determine the appropriate dose of insulin to take in order to avoid being in either a hyper- or hypo-glycaemic state. This is particularly important if you have been infected with SARS CoV-2. #### **Cardiovascular disease** The highest numbers of patients who have been hospitalised with severe or chronic COVID-19 have had [hypertension](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hypertension/) or another type of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Autopsy results from patients who have died with or from the disease show evidence of [myocarditis](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/myocarditis/), defined by the presence of unusual inflammatory cells in the heart. Individuals hospitalised due to the infection also show markers of cardiac injury in their blood and this is seen in patients with and without a pre-existing history of CVD, suggesting that the virus puts pressure on the heart muscles, even in those with no known prior heart issues. Heart failure can occur when your heart muscle doesn’t pump blood as efficiently as it normally does. When combined with [arrhythmia](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/arrhythmia/), which is a common feature seen in vulnerable individuals infected with SARS CoV-2, it puts pressure on the heart and affects how well it functions. There are recent findings that suggest that blood clotting events which are a characteristic of COVID-19 disease progression, are also responsible for some of the cardiovascular events observed in individuals who have died from the infection. This is supported by evidence suggesting that individuals who are on blood thinning medication have significantly improved survival rates compared to those who are not on medication. It is well established that [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) contributes to cardiovascular disease progression. Perpetual [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) can also damage the heart muscle and exhaust the immune system. Having a compromised heart and a dysfunctional immune system are likely to be the main contributory factors leading to cardiac failure in COVID-19 patients. #### **Chronic Lung Conditions** Having long-term conditions that result in recurrent [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) in the lungs such as asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder (COPD), and [cystic fibrosis](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cystic-fibrosis/) (CF) make individuals more susceptible to respiratory lung infections. The lungs are home to specialised white blood cells which help to protect them from inhaled pathogens and toxins under normal circumstances. However, individuals who have compromised lungs, either due to perpetual [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) or abnormal function of the epithelium in the lungs, may result in a state of immune and tissue exhaustion and damage; making the lungs more vulnerable to infection or challenge. In addition, controlling lung [inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) in individuals with chronic or acute asthma may require the individual to use [immunosuppressive medications](#immunosuppressive) such as steroids, which will dampen the immune response and make them more vulnerable to infection. In general, the more chronic the condition, the more likely that a person is compromised, either due to long term medication use or as a result of the pressure the disease poses on lung tissue. Individuals with CF are at a high risk of developing other lung complications because the disease is caused by a genetic dysfunction which affects the level of salt in cells. This leads to water imbalance which can clog up highly vascular organs such as the lungs and digestive tract. In the lungs, this affects the air flow in and out of the lungs, resulting in respiratory distress. As COVID-19 is predominantly a respiratory disease, not having the necessary protection mechanisms in place within the lungs puts individuals at a higher risk of developing severe respiratory disease if infected with SARS CoV-2. You should continue to take your medications but take extra care to protect yourself. If you are a smoker, it is highly recommended you stop smoking to give your lungs a better chance to control and recover from the infection (see [smoking](#smoking) section). #### **Cancer** Blood cancer is caused by a dysfunction in white or red blood cell production from the bone marrow or lymph nodes. Leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma are white blood cell cancers. The white blood cells normally fight infections, and if they are dysfunctional, your body is less able to fight infections efficiently. Polycemia vera is a rare cancer and a type of red blood cell cancer. The red blood cells help to carry oxygen to the rest of your body. Having any cancer of the blood puts you at a higher risk of experiencing severe symptoms once infected with SARS CoV-2. Cancers that affect other major organs, such as the lungs, kidneys or liver also place individuals at a higher risk, as those organs are unable to function properly if malignant. The fact that COVID-19 is a respiratory disease means that those with compromised lungs, either due to cancer or other conditions, are likely to be severely affected if infected. See the [lung](#lung), [liver](#liver) and [kidney](#kidney) sections of this report. In general, people who have cancer are immunosuppressed either due to the cancer itself or the treatment they are undergoing. Individuals with stable disease may wish to discuss the option of delaying [chemotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/chemotherapy/) or elective therapy with their oncologist until the threat of COVID-19 is reduced. Individuals with progressive, aggressive or metastatic disease requiring treatment should take extra caution to protect themselves and self-isolate. See [immunosuppressive treatment](#immunosuppressive) section for further information. #### **Liver Disease** Having chronic liver disease may put you at risk of experiencing severe symptoms once infected with SARS CoV-2. Compromised blood liver functions are a common feature in individuals who are critically hospitalised with COVID-19. The liver is an essential [detoxifying](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/detoxifying/) organ. Its primary function is to filter blood from the digestive tract and the rest of the body. The liver also stores and releases glucose as needed, makes [cholesterol](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/cholesterol/), and stores [iron](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/iron/). The liver holds certain types of white blood cells, and supports immune function by clearing infections. Liver disease involves a process of progressive destruction and regeneration of the liver, often leading to scarring and permanent damage. This progressive liver damage often causes a dysfunction in [metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/), leading to [insulin resistance](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/insulin-resistance/) or impaired insulin production (see [diabetes](#diabetes) section). This in turn affects the immune system and the ability of the body to clear infection, thus hindering the way the body responds to infectious pathogens such as SARS CoV-2. #### **Kidney Disease** As more data emerges on the clinical characteristics of individuals who have been hospitalised or who have died from COVID-19, it is becoming apparent that the most affected organs, after the lungs, are the kidneys. Kidney disease occurs when the kidneys are unable to filter out water and waste from the blood effectively. The filtration of waste products is a natural part of the metabolic process; therefore, factors such as medication, environmental pollution and infection that add to waste generation, also add to the pressure on the kidneys to work efficiently and effectively. Kidneys have historically been thought of as organs that are unable to regenerate, but new research shows that they do have regenerative capabilities, but this process is likely to be slow. As cellular turnover slows down naturally with age, and because age is directly associated with acquisition of kidney disease (see [age](#age) section), recent reports from the USA show that most of the COVID-19-related deaths to date in individuals over 65 have concurrent kidney failure as the main cause of mortality. If compromised kidney function means that the body is not able to effectively filter invading pathogens and toxins, infection with SARS CoV-2 will put additional pressure on the kidneys, potentially leading to kidney damage and toxic shock which will require immediate hospitalisation. Individuals with NCDs such as kidney disease should take their conditions very seriously and talk to a designated healthcare provider about putting appropriate measures in place to protect themselves. Maintaining good hydration and a healthy lifestyle is key. ### **Other factors** #### **[HIV](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hiv/)/ AIDS** Testing positive for Human Immunodeficiency Virus ([HIV](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hiv/)) does not make you more susceptible to developing severe COVID-19 symptoms, provided you are on effective [antiretroviral](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/antiretroviral/) treatment. However, if you are not on appropriate treatment, the [HIV](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hiv/) virus is free to attack your immune system, putting you at a higher risk of developing AIDS. AIDS stands for Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome. As the name indicates, this is a progressive condition that results in destruction of the immune system. Without a functioning immune system, you will become immunocompromised, meaning that it will be more difficult for your body to fight an infection. This increases the likelihood of you experiencing more severe symptoms, should you become infected with SARS CoV-19, of. If you have [HIV](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/hiv/) you should already be under care of an appropriate healthcare provider who can properly monitor your condition. #### Smoking Tobacco smoke exposure increases susceptibility to respiratory tract infections such as COVID-19. Smoking is known to damage the lungs and airways which causes a range of severe respiratory problems (see [chronic lung conditions](#lung)), it also puts you at a high risk of developing lung cancer and [cardiovascular disease](#CVdisease), the latter is the risk factor most frequently seen in those individuals who have died from COVID-19. Smoking does not only directly affect you, it also puts those around you who are exposed to secondhand smoke at risk. In light of the current pandemic, there has never been a more important time to stop smoking, not only for your own health, but also to protect those around you. If you are using e-cigarettes or other ‘vaping’ devices, recent clinical and scientific evidence has suggested that these pose a similar threat to the health of your lungs and heart. E-cigarettes contain chemicals that are not present in traditional cigarettes, but which have additional health implications associated with them. E-cigarettes also carry an additional hygiene risk due to reuse of mouth pieces, which means you are more likely to expose yourself to pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2, which can survive on a variety of surfaces. #### **Immunosuppressive medication or treatment** There are many medications, treatments and medical procedures that can temporarily reduce the ability of your immune system to fight infection. In this section, we will provide a few examples; however, if you are on any medication or have undergone a medical procedure recently which makes you immune compromised, you should be in regular contact with your healthcare provider. They will be able to determine how vulnerable you are to acquiring severe or critical COVID-19 symptoms and advise you which steps to take to reduce your chances of catching this, or any, infection. * **Immunosuppressants** Drugs that suppress the immune system such as certain biologics (recombinant proteins) and glucocorticoids (steroids), inhibit white blood cells activity or function. These cells are the main fighters of infection in the body and, therefore, taking drugs that stop them from working effectively or reduce their numbers, affects the ability of the immune system to fight infection. This makes you more susceptible to severe symptoms following infection with SARS CoV-2. * **[Chemotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/chemotherapy/)** One of the most widely used treatments for cancer is [chemotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/chemotherapy/). The mechanism of chemotherapeutic agents is to destroy rapidly growing cells by damaging DNA and other factors involved in cell division. Because of its mechanism of action, [chemotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/chemotherapy/) also attacks the highly dividing and healthy cells of the body such as the [stem cells](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/stem-cells/) of the bone marrow. These [stem cells](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/stem-cells/) are responsible for providing a continuous supply of the disease fighting, white blood cells. During and immediately after [chemotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/chemotherapy/) your body is less able to defend itself against infection. Individuals who have certain types of [cancer](#cancer) may already be at an increased risk of experiencing severe COVID-19 symptoms; and if the same individual is also undergoing [chemotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/chemotherapy/), extra protection and caution should be considered. * **Bone marrow transplantation** is a procedure that aims to replace otherwise damaged or destroyed bone marrow with healthy bone marrow. The first step involves [radiotherapy](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/radiotherapy/) to partially or completely eliminate faulty [stem cells](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/stem-cells/). The aim is to reintroduce healthier bone marrow via a transplant. As described above, the bone marrow is an essential source of infection-fighting white blood cells. The period between bone marrow elimination and transplant acceptance (i.e. the body adjusting to its new, healthier bone marrow) is around 6 weeks, and this can vary from person to person. During this critical time, a transplant recipient is at extremely high risk of acquiring infections. This includes infection with SARS CoV-2. #### **Living in a care facility or nursing home** Nursing home populations are at the highest risk of being affected by COVID-19 compared to the general population because they have a high proportion of [older](#age) adults who are often living with underlying chronic medical conditions which puts them at risk of experiencing severe or chronic symptoms if infected with SARS-CoV-2. To protect all who live and work in nursing homes and care facilities, regular cleaning and disinfection of common areas, appropriate [social distancing](https://nabtahealth.com/what-is-social-distancing/), and self-isolation measures where required, should be implemented. It is important that carers, who may carry the virus but may not be at risk themselves, also take the necessary steps to protect those residents who are considered high risk. This includes social distancing as much as possible and wearing appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). #### **Working in a healthcare environment** Being a doctor, nurse or an individual working in a hospital or clinic means that you may have regular exposure to patients who may have tested positive for SARS CoV-2 and, therefore, there is a risk of them passing the infection on to you. Take sensible precautions when handling infected patients; use PPE when at work, such as masks, a clinical coat/suit and gloves, and ensure that it is changed on a regular basis. Outside of work, take steps to protect yourself and those around you who may be vulnerable to infection. Use best practice for maintaining hygiene, including removal of potentially contaminated clothing whilst still at work, washing hands with soap and water, and disinfecting any other materials that may come in contact with others outside the hospital setting. #### **Contact with an infected or exposed individual / environment** Being in close contact with someone who has COVID-19, or someone who has been exposed to the SARS CoV-2 virus, puts you at high risk of infection, which is increased if you have other confounding factors, such as those mentioned in this article. Because the majority of individuals who are exposed to the virus do not display obvious symptoms, extra care to protect yourself should be taken if you are in a high risk category. Based on current data surrounding the length of time the virus remains in our bodies (the incubation period), you should self-isolate for at least 14 days from the time of potential exposure (Day 0) to minimise passing the infection to others. ### **Conclusion** As this article shows, many of the factors that result in an individual becoming ‘high risk’ occur as a result of underlying health conditions. Therefore, it is important to ensure that your current health status is under control and that medication, where required, is taken appropriately. Being aware of the signs of infection such as a fever, cough, shortness of breath, is key. Call ahead before visiting a health care provider or emergency department to alert them to the fact that you have been exposed to the virus. If you are in a country which has implemented tools to alert or monitor infected or potentially infected individuals, you may wish to adopt some of those tools to protect those around you and reduce the chance of cross contamination. The general recommendation is to limit hospital visits and contact with healthcare facilities where ever possible. If you have a chronic condition and require ongoing medical care or monitoring, provided your doctor is okay with it, consider using telehealth, electronic consultations and remote care, as appropriate. If you are considered high risk and require medications or a pharmacy visit, think about asking others who are less vulnerable to pick up what is needed. It is important to keep taking your medications as recommended. Nabta Health is committed to providing you with the most up to date, peer-reviewed, clinically- and scientifically-validated information on COVID-19 and other conditions. If you are not sure what your, or your loved ones’, risk factors are, Nabta Health has built a risk assessment questionnaire, which can be accessed from our Application. The Nabta App can be downloaded from our website ([www.nabtahealth.com](http://www.nabtahealth.com)). **References:** * [https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html](https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html) * Madjid, M., _et al_. Potential Effects of Coronaviruses on the Cardiovascular System: A Review. _JAMA Cardiol._ Published online March 27, 2020. * Ruparelia, N., _et al._ Inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease: a route to targeted therapies. _Nat Rev Cardiol_ 14**,** 133–144 (2017) * Libert, C.,_et al_. The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. _Nat Rev Immunol_ 10, 594–604 (2010) * ue Tsai, Xavier Clemente-Casares, Angela C. Zhou, Helena Lei, Jennifer J. Ahn, Yi Tao Chan, O.C., et al. Insulin Receptor-Mediated Stimulation Boosts T Cell Immunity during [Inflammation](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/inflammation/) and Infection. _Cell [Metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/)_ 28 (6), 922-934 (2018) * Muniyappa, R. and Gubbi, S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. _Am j physiol. Endocrinology and [metabolism](https://nabtahealth.com/glossary/metabolism/)_ 318(5), E736-E741. (2020) * Hanna, T. P. _et al_. “Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic. _Nature rev clin oncol_ 17(5) 268-270. (2020) * [https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf](https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf) * Jafar, N., _et al_. The Effect of Short-Term Hyperglycemia on the Innate Immune System. _Am J of Med Sci_, 351 (2), 201-211 (2016) * Cheng, Y., _et al_. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. _Kidney int._ vol. 97 (5), 829-838 (2020) * Parohan, M., et al. Liver injury is associated with severe Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of retrospective studies. _Hepatol Res_. (2020) * [https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html](https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html) * Ishan, P., _et al_. Association of Treatment Dose Anticoagulation with In-Hospital Survival Among Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J Am College Cardiol. (in press) (2020).